0. Preface

In my last article here (German) I explained that today's main challenge (many call it “digital transformation”) facing almost all companies is not digital, but an organizational one. It also has nothing to do with digital business models, like many want to believe.

This comprehensive guide will cover a phenomenon called “disruption”, explain how it impacts successful organizations and what they need to do in order to embrace it and become disruptors themselves. As such, I will address the following:

- Why almost everyone around you is misusing the term “disruption” and has been misapplying it for years.

- We will explore why Blackberry, one of the most successful smartphone manufacturers was disrupted, why they didn’t see it coming and what contributing factors led to the inevitable outcome.

- Explain why it’s not that simple for companies to just disrupt themselves (especially very successful ones) and why this is not a rational strategy.

- Point out how many executives (sometimes) willingly ignore and fail to recognize the predictable patterns of disruption, missing out on the opportunity to capitalize on it.

- We will look at another example about integrated steel mills, dominating the steel industry for decades, that were blindsided and overrun by an initially inconspicuous technology and why they only saw disruption coming after it was too late.

- Illustrate the reasons why highly successful incumbents get disrupted by innovations in a predictable fashion, simply for doing everything right (e.g. listening to customers) and how they become prisoners of their own success.

- Look at how German SMEs approach disruption and what defensive strategies they employ.

- Reveal why doing the right thing is extremely hard to sell to people in charge.

- Show you the leading causes of the demise of these industry giants by illustrating how a startup in the heating industry successfully disrupted its incumbents and reveal their secrets to success.

- Highlight various product and organizational strategies your company can use to solve the dilemma and advert being disrupted.

Be forewarned: This is not a quick read. Instead, it’s a very comprehensive guide packed with many useful insights and key takeaways throughout this guide. But rest assured, I’ll explain the basics and the mechanisms at play along the way and will simplify concepts where needed, so that readers, who might not be fully proficient in this domain, get the same benefits as industry experts.

There’s a lot to be covered, so grab yourself a cup of caffeinated beverage of your choice and let’s get started…

1. Defining “Disruptive Innovation” and Why Almost Everyone around You Is Misusing the Term

Before we discuss disruption innovation in detail, we need to first have a clear understanding what it actually means. If you think you already know, then let me ask you the following questions:

- Would you consider the first automobile to be a disruptive technology?1

- And would you consider Uber2 disruptive?

If your answer is “no” to either question, then you can skip this part (if you so choose), as it seems you already have a good understanding of the definition that the godfather of innovation Clayton M. Christensen came up with. If your answer is “yes” to either question, then the following should prove to be very insightful for you. And you’ll have a much better grasp of what the concept of disruption really means than 90% of the people that use the term in daily business.

The term was first coined and defined by Clayton M. Christensen, famous for his seminal book “The Innovator's Dilemma” published in 1997. Today his concept of “disruptive innovation” is present in our everyday language about innovation.

ronically, disruption theory is becoming a victim of its own success. Despite its broad usage, the core concepts have been widely misunderstood and its basic principles have been misapplied.3 I’m always shocked by how loosely the term is tossed around or how people roll their eyes at the mere mention of “disruption”. This is in part due to sloppy references from writers and journalists. And to make matters worse, it seems they haven’t read a serious book or article on the subject. Oftentimes, startups and even consultants use the term vaguely to invoke the concept in support of whatever it is they wish to sell or convey, even though their product or service just simplifies an existing technology, not displaces it.

”You're not that disruptive. Stop lying to yourself!”

— Rameet Chawla

By misunderstanding this one critical term, we lose much of the understanding and power of the innovator’s dilemma. This is similar to German companies using the term “Digital Transformation”. Everybody uses it, almost nobody can give you an accurate definition. And even if they did, they would come to understand that “Digital Transformation” does not solve the problems of today's companies in a VUCA world.

Furthermore, if we use “disruptive innovation” to describe any situation in which an industry is shaken up and where incumbents fall, this usage would be much too broad. Applying the concept correctly matters and is critical in order to realize its benefits. A small competitor that steals small parts of your market share can likely be ignored, unless they’re on a disruptive path, in which case it could be a very fatal threat to your company. However, both of these challenges need to be addressed fundamentally different!

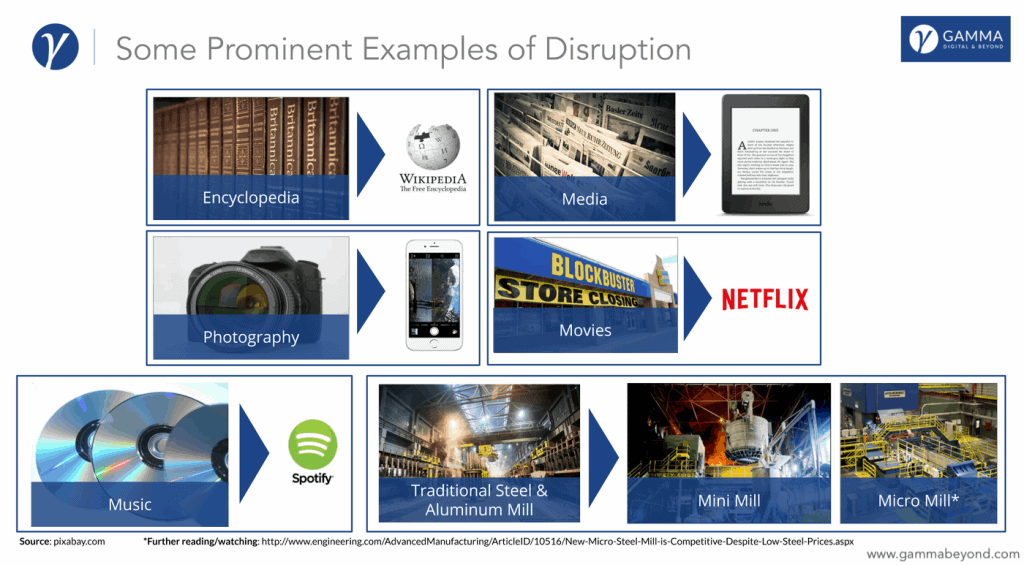

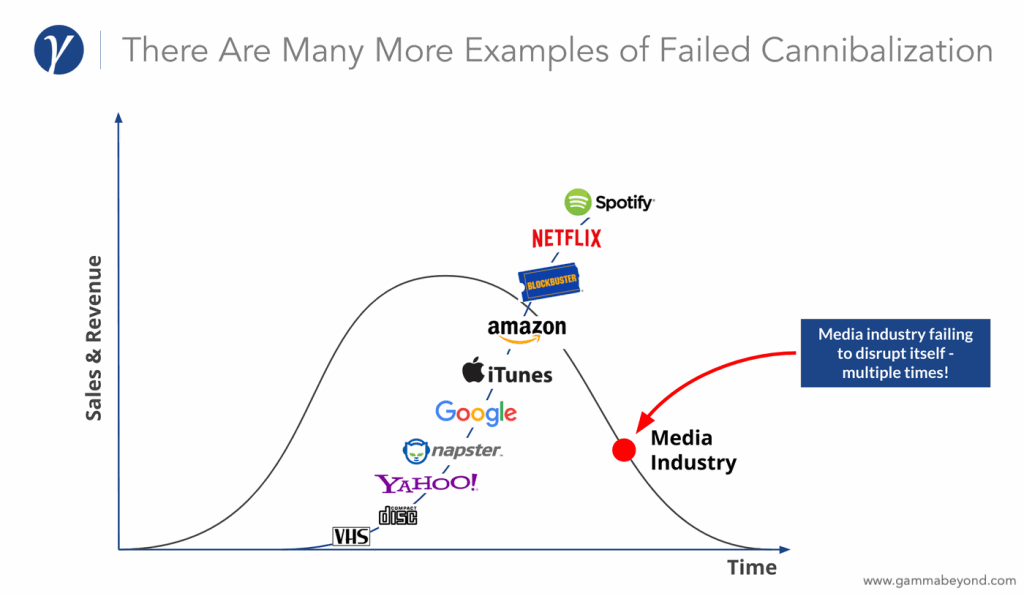

The concept of disruptive innovation is used to describe technology that uproots, and eventually replaces, an existing technology (e.g. video streaming eventually replacing video rentals).

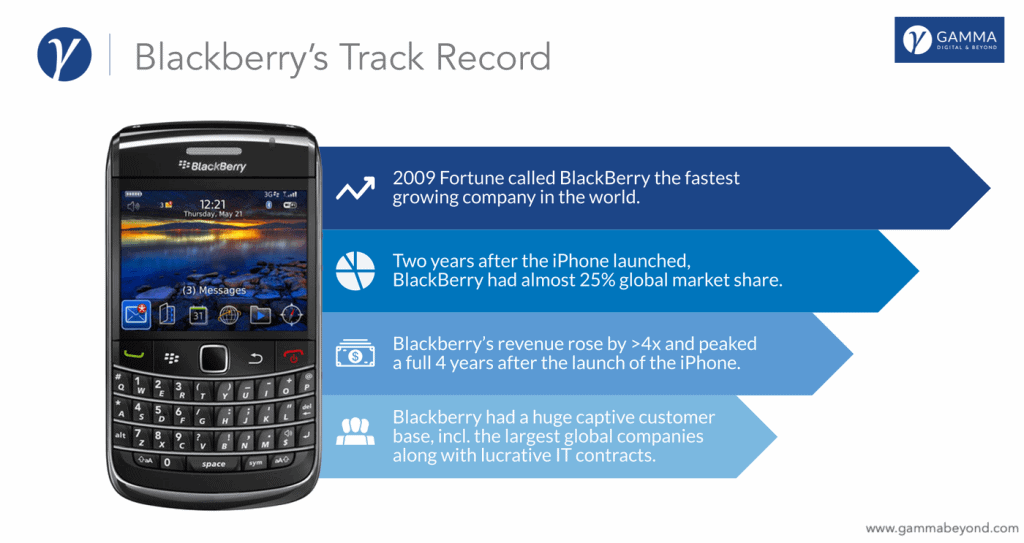

Making the Distinction between Sustaining, Breakthrough and Disruptive Innovation

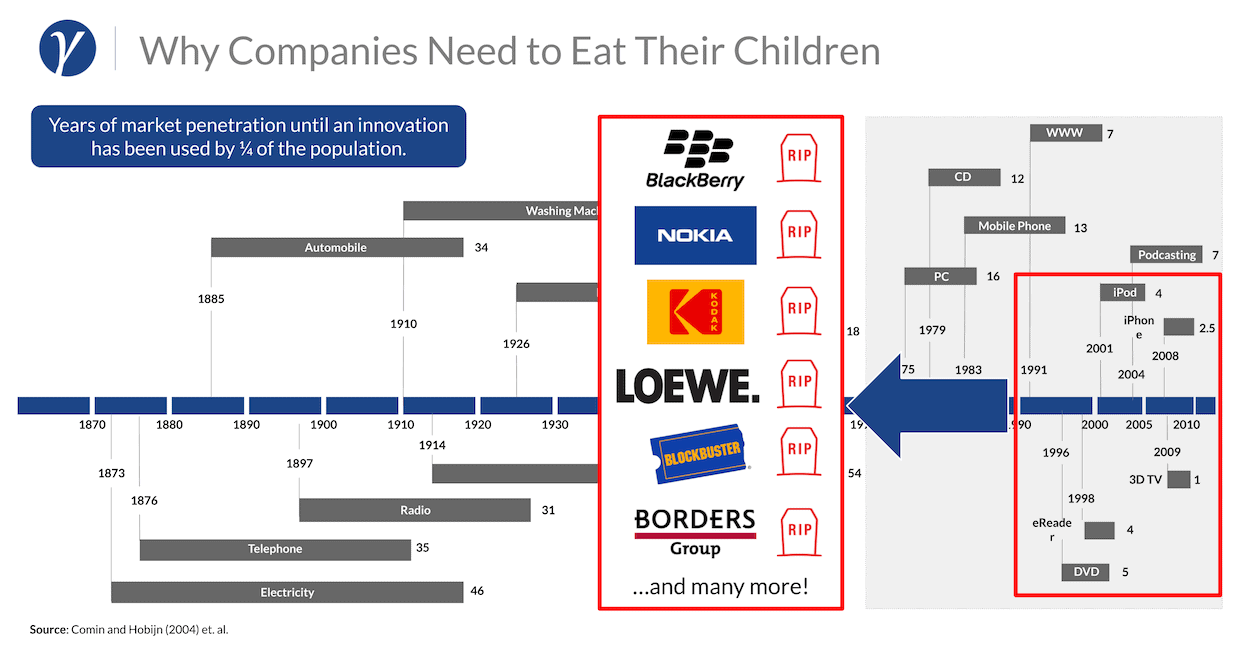

In order to correctly identify which innovation types we’re dealing with, we need to talk about the three types of innovation. These will also be the definitions I will use throughout this article to stay consistent, as to not lose the power of the concept.

Sustaining (or incremental) innovation is continuous technological improvement to an existing product, service or process within the context of your existing business model. The goal is to do what you already do better e.g. three-bladed razor becoming a five-bladed one. Generally, the lion's share of innovation that happens in companies fall into this category.

A breakthrough (or radical) innovation is a change to an existing product, service or process that has a significant impact on the business, but still fits within the company’s business model. Think of the Motorola Razr. Even though it was a clamshell, it pushed the boundaries of design and was a runaway success for Motorola. This sometimes allows companies to leapfrog ahead of its competition, but the innovation stays within the core offerings.

Finally, disruptive innovation is a new product, service or process that either creates a new market or enters at the bottom/low-end of the market and is initially considered inferior to the existing offering as it moves up and displaces established incumbents e.g. streaming services such as Spotify or Netflix displacing the CompactDisc.

”The electric light did not come from the

continuous improvement of candles.”

— Oren Harari

The main reason “disruptive” causes so much confusion is that it sounds like a “major upset”, which seems to suggest that the technological cause should be major as well. This in turn, leads many to falsely believe that disruptive innovation coincides with technically radical innovation. So people end up confusing disruptive with radical innovation. The opposite of disruptive is sustaining.

A disruptive innovation may or may not represent a radical innovation. Also, a radical breakthrough may or may not be disruptive, while an incremental innovation can be extremely disruptive. In fact, most documented cases of disruption originated from an incremental change that was well within the technical capabilities of the incumbent. On the flip side, companies have also taken huge risks and engineered extremely complex new innovations that were hugely successful with their existing mainstream customers, but are considered sustaining e.g. Boeing 787.

Key Takeaways

- The basic concept of disruption theory has been widely misunderstood and its principles misapplied, losing much of the power of the innovator’s dilemma.

- Innovation generally comes in three flavors: sustaining, breakthrough and disruptive.

- Disruption has little to do with technology per se.

- Disruption is a process. It doesn’t refer to a product or service at one fixed point, instead it’s an evolution of that product or service over time, which, in some cases can take decades.

- Disruption is relative to the industry. An innovation can be sustaining in one industry, but disruptive in another.

- Disruption originates from two types of markets - low-end or new-market. Low-end disruptors start with a “good enough” product at the low-end of the market. New-market disruptors create a market where none existed before.

- If we get sloppy with our definitions or fail to apply the concept correctly, we may end up using the wrong tools and strategies for a given context, reducing our chances of success.

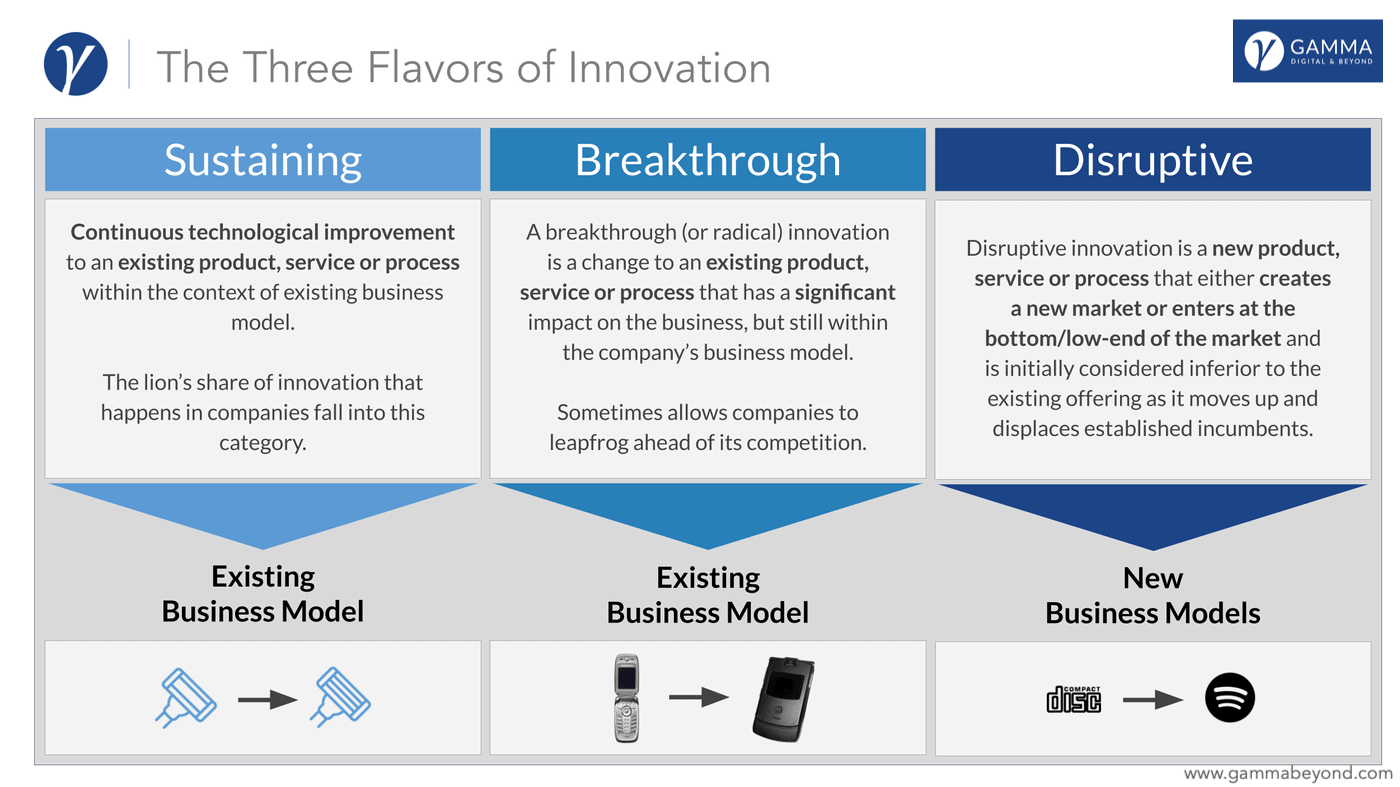

2. The Rise & Fall of BlackBerry

I would like to continue this guide by highlighting a real-life example that most readers are familiar with - two smartphone manufacturer Apple and Blackberry (also known as RIM or Research in Motion). Together we will deconstruct the challenges these companies faced, explain some basics models, deduct the learnings that can and should be drawn from these examples and see how these learnings can be applied.

2.1 Enter BlackBerry…

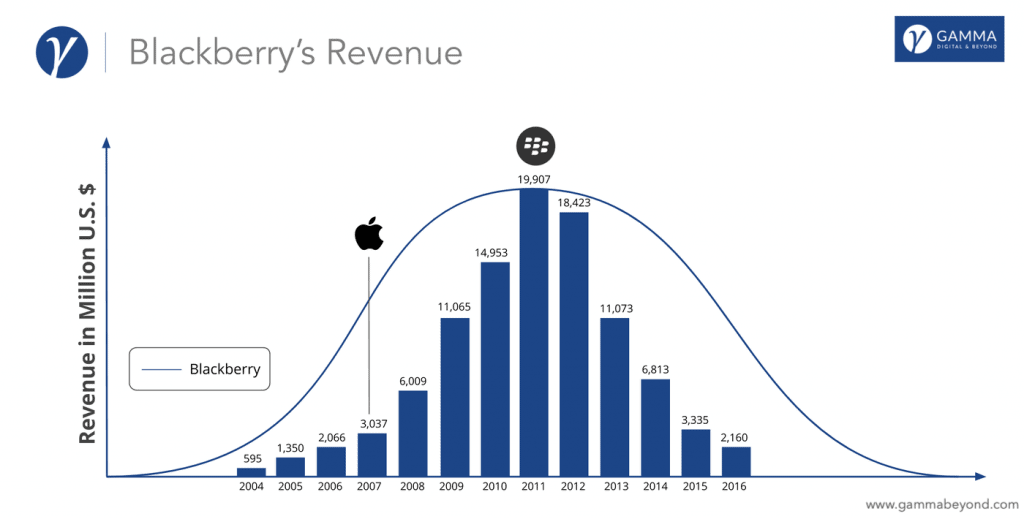

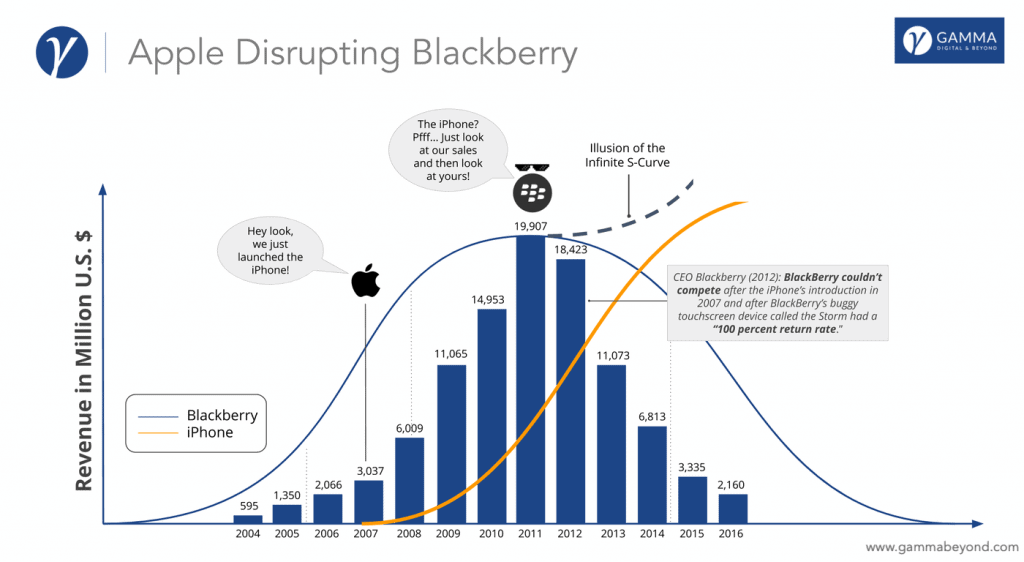

In 2009, two years after the iPhone launched, Fortune called BlackBerry the fastest growing company in the world. With its huge captive customer base (growing >80% in the same year) incl. some of the largest global companies along with very lucrative contracts, BlackBerry commanded almost 25% global market share (and 56% market share in the U.S.). Blackberry’s revenue rose even further by over 4x and peaked a full 4 years after the launch of the iPhone (see graph below).

“There’s no chance that the iPhone is going

to get any significant market share. No chance.“

- Steve Ballmer, CEO of Microsoft, 20074

How did Apple do? Well, it took 39th place in Forbes magazine's top-100 list.

How did Apple do? Well, it took 39th place in Forbes magazine's top-100 list.

But then in early 2017, Gartner reported that Blackberry had an official global market share of 0.0%. Well, at least it couldn’t get worse, right?

If, at this point you’re confused, and you’re asking yourself if Blackberry really only died in 2017 and not earlier, don’t be. Let me explain…

2.2 The Fatal Fallacy of Following Lagging Indicators

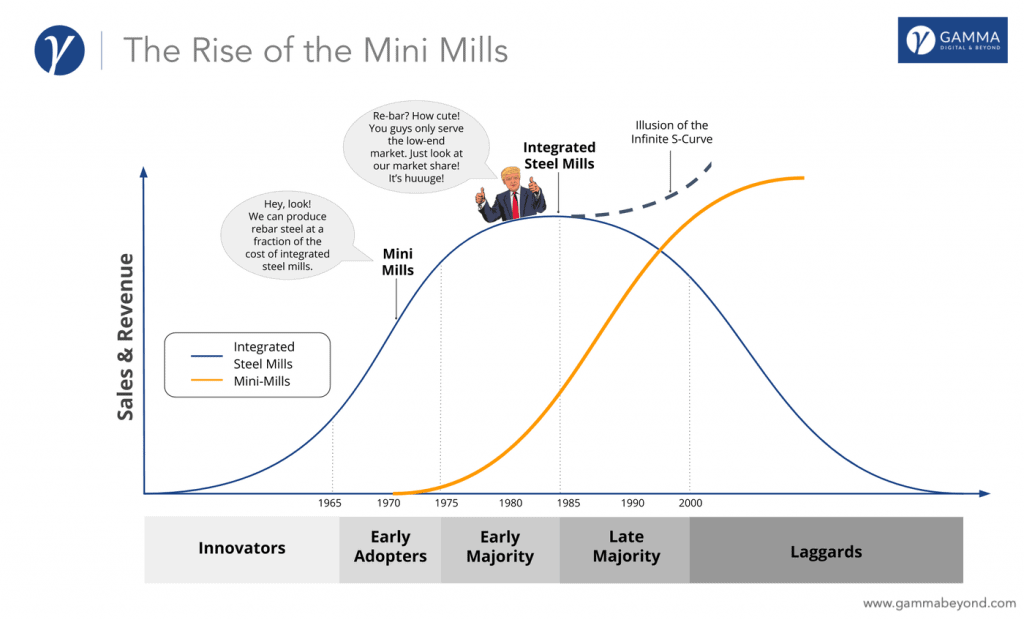

Revenue (along with profits) tend to be what economists call a “lagging indicator”. Lagging indicators can confirm long-term trends, but they do not predict them. Blackberry also fell prey to the ”Illusion of the Infinite S-Curve”5, essentially believing the growth would continue indefinitely. In reality, Blackberry actually had its death sentence back in 2007 when the iPhone was introduced, as Blackberry’s CEO admitted as early as 2012:

“…BlackBerry couldn’t compete after the iPhone’s introduction in 2007 and after BlackBerry’s buggy touchscreen device called the Storm had a “100 percent return rate.”

Then, why didn’t Blackberry just disrupt itself?

2.3 To Disrupt or to Get Disrupted - That Is the Question!

After Apple entered the market it consumerized and thus pioneered the smartphone industry, by ushering in a paradigm shift from the enterprise to the still insignificant consumer market.

The chances of Blackberry disrupting its entire product portfolio and hugely profitable business model, with its large customer base and long-term contracts, in order to adapt to the rapidly changing industry, were slim to none. So from a CEO’s perspective disrupting oneself can be viewed as “irrational”. I’ll explain later on in detail why it is so hard for established companies to disrupt themselves, especially when they’re successful.

So, the only other option left for Blackberry was to get disrupted by another player - in this case Apple. By the time Blackberry fired its CEO and had consumer products in their pipeline, the race had already been won. And the rest is history…

Coincidental side note: At roughly the time, a similar, futile battle was emerging among the big media companies and Netflix.

Time Warner CEO on Netflix:

“It’s a little bit like, is the Albanian army going to take over the world?”

— Jeff Bewkes, CEO of Time Warner back in 2009

For those interested, or for those wanting additional bonus points, I highly recommend you read the NYT article ”Time Warner Views Netflix as a Fading Star”, as it serves as another cautionary tale of disruption.

But, before we can answer the question why companies get disrupted in an almost seemingly predictable fashion, we’ll need to cover some basics first.

2.4 The Timeless Truth About the (Technology) Product Life Cycle

The technology product life cycle is very predictable, actually, embarrassingly so. The shape of the technology life cycle is also referred to as an S-Curve. Oftentimes, you’ll hear it called the S-Curve of innovation and in the interest of your reading pleasure, I will use these terms interchangeably throughout this article.

The S-Curve is a robust framework that is backed up by decades of empirical evidence and has helped researchers to understand the successes and failures in countless industries.6 Some of the most important stages through which a product cycles through are as follows7:

1. Introduction (Example: Holographic Projection)

After a product has been developed (R&D stage) for a particular need of customers, it is introduced into the market. As the product tries to find product-market fit and production is being ramped up, its demand is consequently low and promotional costs are high. Simply put: the product burns more cash than it generates. Sometimes this stage is also called the "bleeding edge”, because the profits are often negative and the prospects of failure are high.

2. Growth (Example: Tablet PCs)

This stage is where the product achieves product-market fit and gains acceptance. It is typically characterized by a rapid increase in sales and profits, due to the benefits from economies of scale in production and the sustained promotional expenditure. This makes it possible for the company to focus its efforts on scaling the product towards the largest possible market and maximize the potential of this growth stage.

3. Maturity (Example: Laptops)

When the product and market enters maturity the rate of growth declines, as the volume of sales keeps increasing. Margins and market share are at its highest and most companies try to maintain their market share they have built up. This is also the stage where the product becomes highly standardized, having seem multiple innovations, and achieves near maximum efficiency in a very competitive space. The product innovation curve now beings to taper off, only seeing incremental improvements being made. As a result, a company needs to spend an increasing amount on sale and promotion.

4. Decline (Example: Typewriters)

By this time disruptors have entered the market, starting at the low-end of the market (often capitalizing on niches) and slowly catching up to their incumbents. Consequently, the sales of the product start declining as the name suggests. This pace increases until the disruptor has reached parity with its incumbents in terms of cost and performance. The disruptor then continues to go “up market” (we will also see this in our mini mills later on) and goes after higher margin markets and products, thus increasing its market share, starting off a whole new S-Curve.

Benedict Evans (Partner at Andreessen Horowitz) summarizes the S-Curve model quite nicely8.

The development of technologies tends to follow an S-Curve: they improve slowly, then quickly, and then slowly again. And at that last stage, they're really, really good. Everything has been optimised and worked out and understood, and they're fast, cheap and reliable. That's also often the point that a new architecture comes to replace them.

He continues by illustrating this with an example (2016):

You can see this very clearly today in devices such as Apple's new Macbook or Windows 'ultrabooks' - they've taken Intel's x86 and the mouse and window-based GUI model as far as they can go, and reached the point that everything possible has been optimised. Smartphones are probably at the point that the curve is starting to flatten - a lot has been optimised but there's still work to do, especially around cameras and battery life, and of course GPUs for VR. That curve will probably flatten out just at the point that AR starts to start shipping.

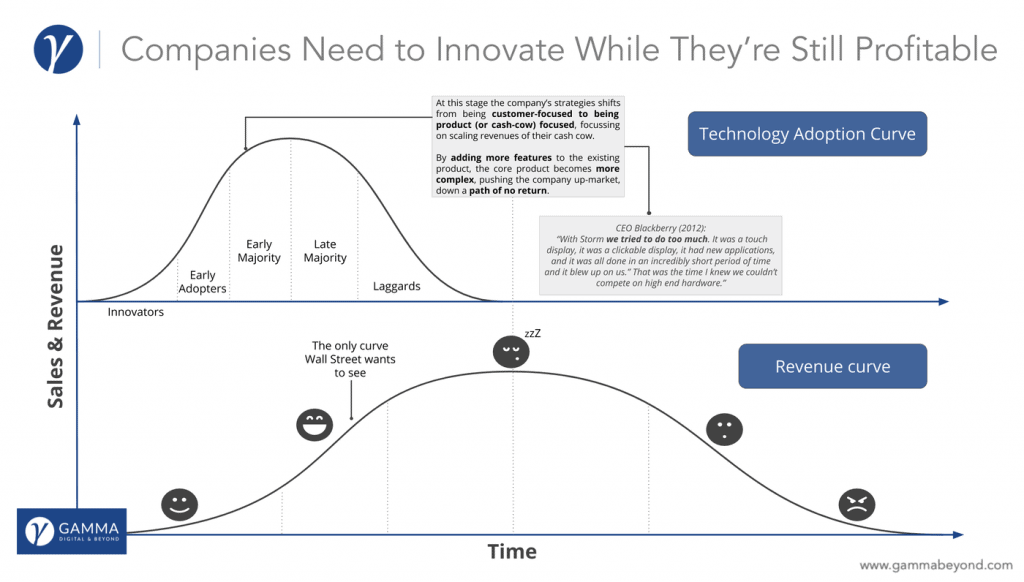

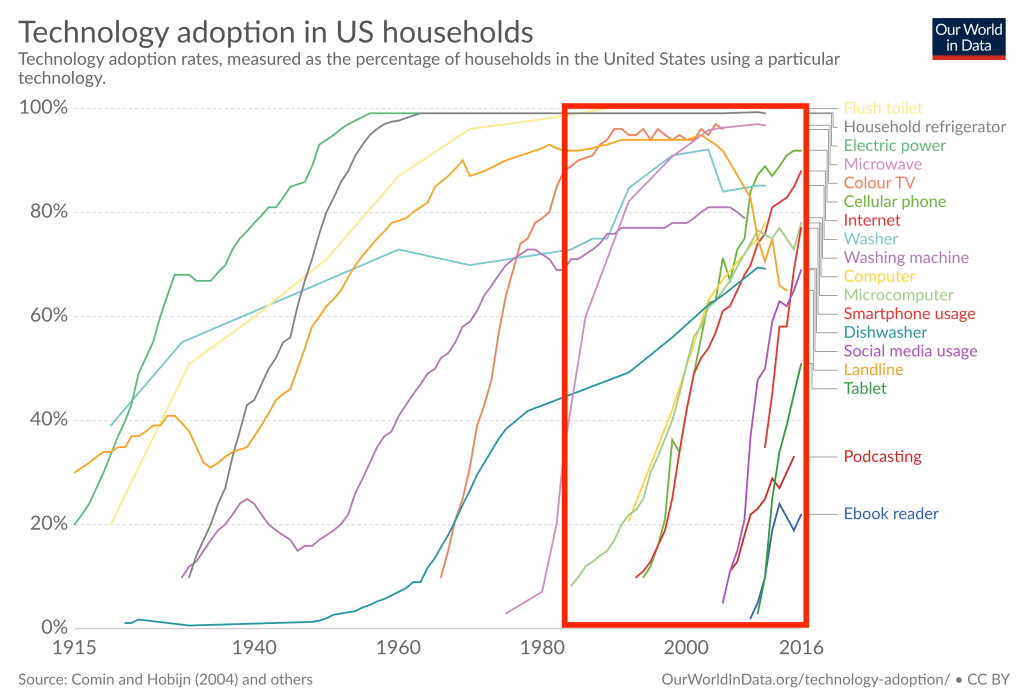

When talking about the S-Curve, we also need to mention the Technology Adoption Curve9 from a user perspective. The adoption curve coincides nicely with the S-Curve. Ironically, the only curve Wall Street is interested in is the revenue curve. As you can see from the illustration below, this singular view is very problematic to say the least. When the product life cycle/technology adoption curve is nearing its end, the revenue curve is typically at its peak - it lags significantly.

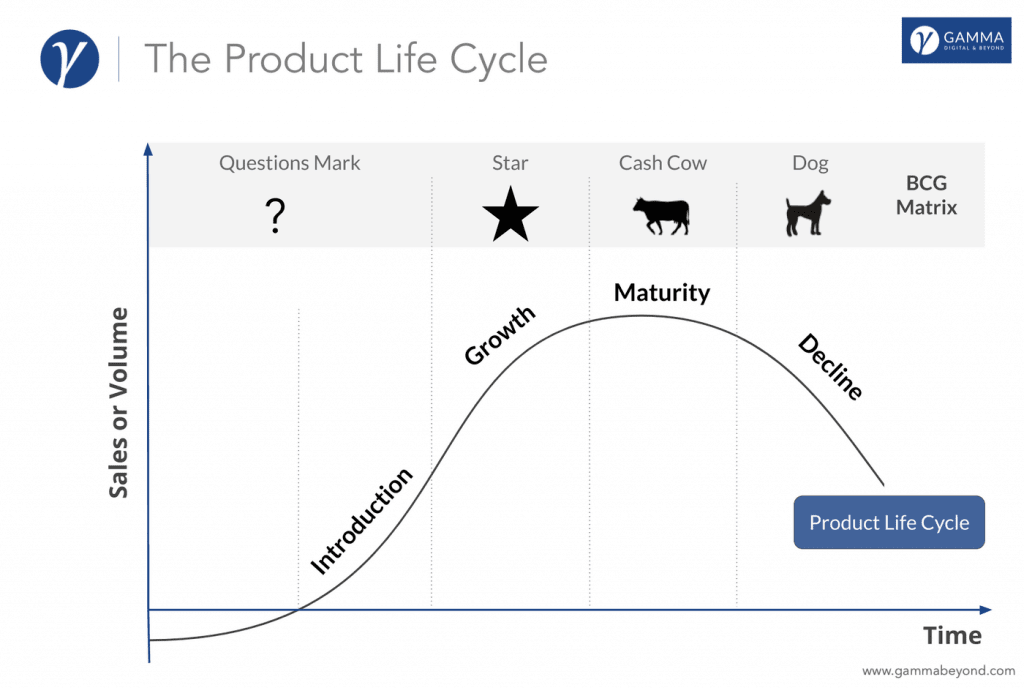

Before we move on, we need to talk about the BCG Matrix, as it’s based on the product life cycle.

2.5 The Small Little Detail Companies Tend to Forget about the BCG Matrix

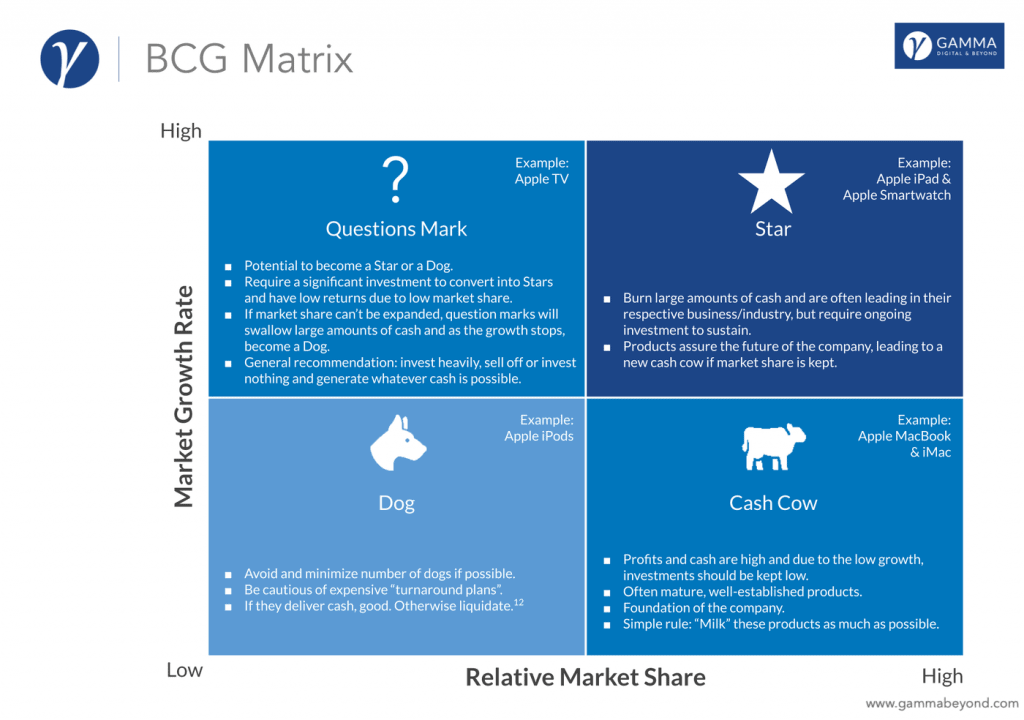

In 1970 Boston Consulting Group (BCG)10 created the BCG-Matrix11, which is based on the product life cycle that we’ve just covered. It is used to determine what priority should be given to a product portfolio within a given business unit. Essentially, the matrix helps managers by visualizing how much cash is being generated versus how much is being burnt, so that the company can allocate its resources accordingly.

To ensure the long-term growth and value creation of a company, it should have a portfolio of products (or services) that contain both high-growth products in need of additional cash and low-growth products that generate a lot of cash.

As illustrated in chart below, the matrix classifies different business units or products into four different quadrants/categories - Stars, Question Marks, Cash Cows and Dogs. This categorization is based on the market growth rate of the industry and the relative market share of the respective businesses, which is relative to the largest competitor present. For that reason, you’ll sometimes hear the BCG-Matrix referred to as a Growth-Share Matrix. If you don’t remember the different BCG categories and their respective function, don’t worry. Find a compact summary in the illustration below.

Following the BCG matrix’s logic, implies that when you’re the market leader in any given mature industry, it’s imperative that you milk your cash cow to its fullest potential. Most companies seem to intuitively grasp this concept. German SMEs (aka “Mittelstand”) in particular, execute the “milking their cash cow” strategy to near perfection.

But what these companies often miss, is probably the most important aspect that determines a lasting and successful company - one that can capture successive S-Curves: The BCG-Matrix clearly states that the cash generated from your Cash Cows should be reinvested into R&D projects and your questions marks.

2.6 The Times They Are a-Changin

As with all models, they are simplified versions of reality. This in turn, doesn’t mean they are not useful, just because they don’t represent the full extend of reality.13 Instead, they should serve as general guidelines and be applied with thought instead of blindly applying them to anything that seems to fit these models. And when considering this, there’s some important aspects we have to take into account, in respect to the BCG-Matrix.

- It assumes that markets are fairly stable environments, where established companies have an incumbent’s advantage. Sure, that may have been true 60 years ago, but that case can hardly be made today.

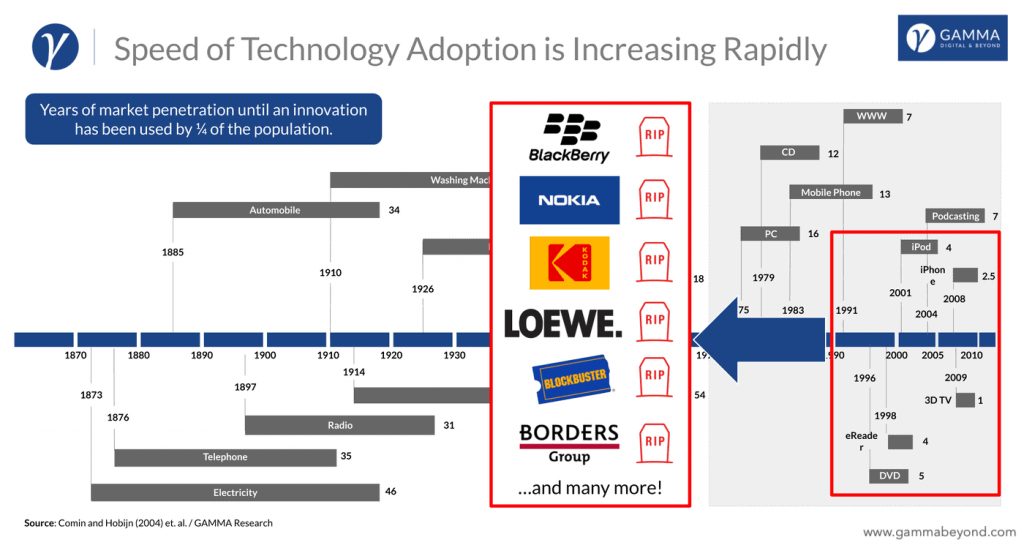

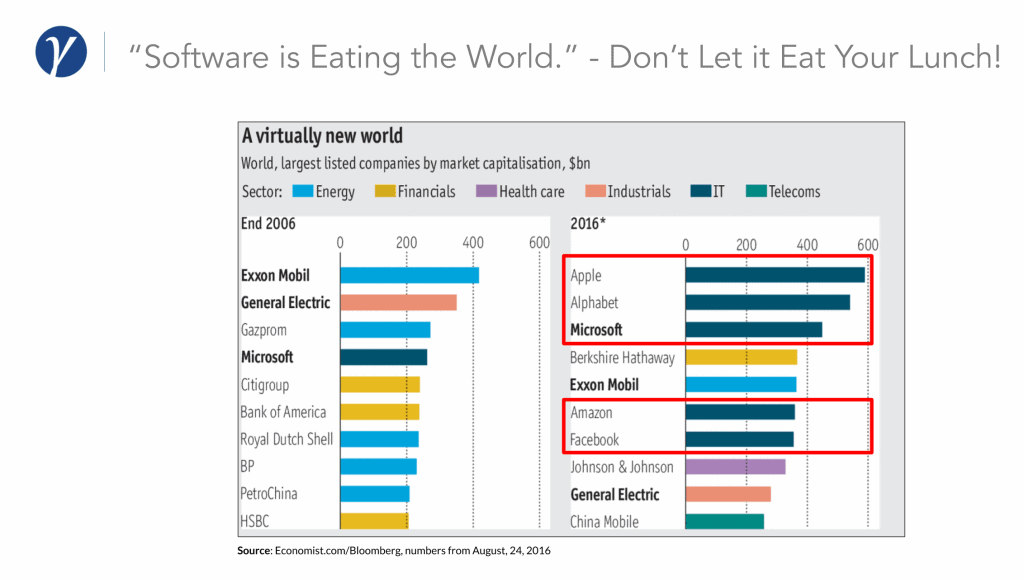

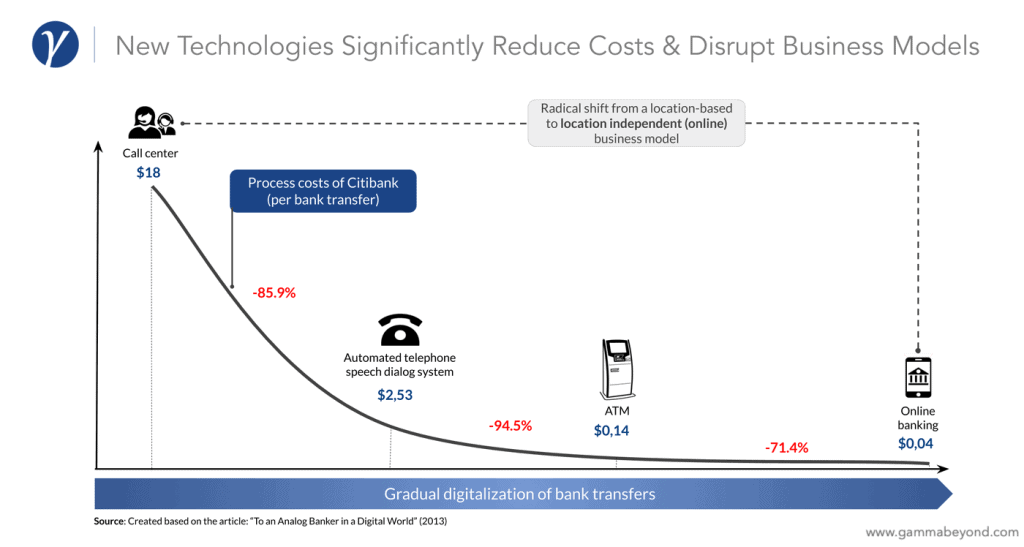

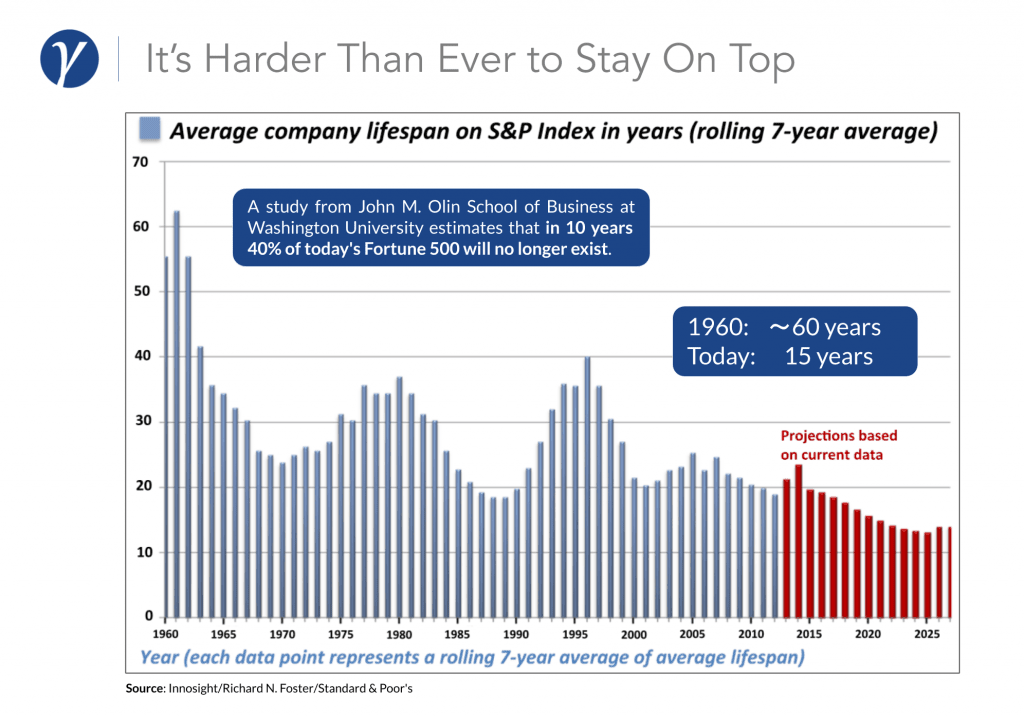

- The speed of technology adoption today is increasing so rapidly, that it’s harder than ever to stay on top (see chart below). And this is only likely to increase in the future.

- Neither market share or company size matters in the age of cloud services. The internet has brought down market entry barriers and distribution costs to almost zero, enabling almost anyone to create highly scalable products.

- As a result, the life cycles curves have become much shorter and steeper.

- Companies that don’t come to grasp with this new reality are dying faster than ever.

Ultimately, this means that when companies think they have a Cash Cow on their hands, it’s probably already too late.

Key Takeaways

- Don’t rely on lagging indicators such as revenue to help you predict what’s coming next. This will almost certainly backfire in the long run.

- Even though the cyclical nature of product life cycles are well understood and have been studied extensively, it’s still shocking how many companies (sometimes willingly) ignore this fact and make themselves prime targets for disruption.

- When the product life cycle is near its end, revenue is commonly at its highest.

- Question Marks (aka problem children) are products that have strong growth, but hardly generate any cash - just like real children.

- Yet, it is these products that enable companies to build more Stars and therefore Cash Cows in the future. Or, to put it bluntly: The only reason for Cash Cows to exist, is to allow you to build new Cash Cows.

- Not only is the speed of technology adoption increasing, but life cycles curves have also become much shorter and steeper, resulting in shorter company lifespans.

- Models are simplified versions of reality and should not be applied blindlessly.

3. Why Bad Things Happen to Good Companies14

As with every good fairy tale (except you’re reading non-fiction at the moment), there’s a dilemma every hero has to face. And in our case it’s the Innovator’s Dilemma that our companies have to content with.

The main problem the Innovator’s Dilemma poses is this:

Highly successful companies that do everything by the book such as listening to customers, supporting their decisions by data and facts, being disciplined about costs and quality etc., get blindsided by innovations that rapidly steal their market share, simply because it was doing everything right.

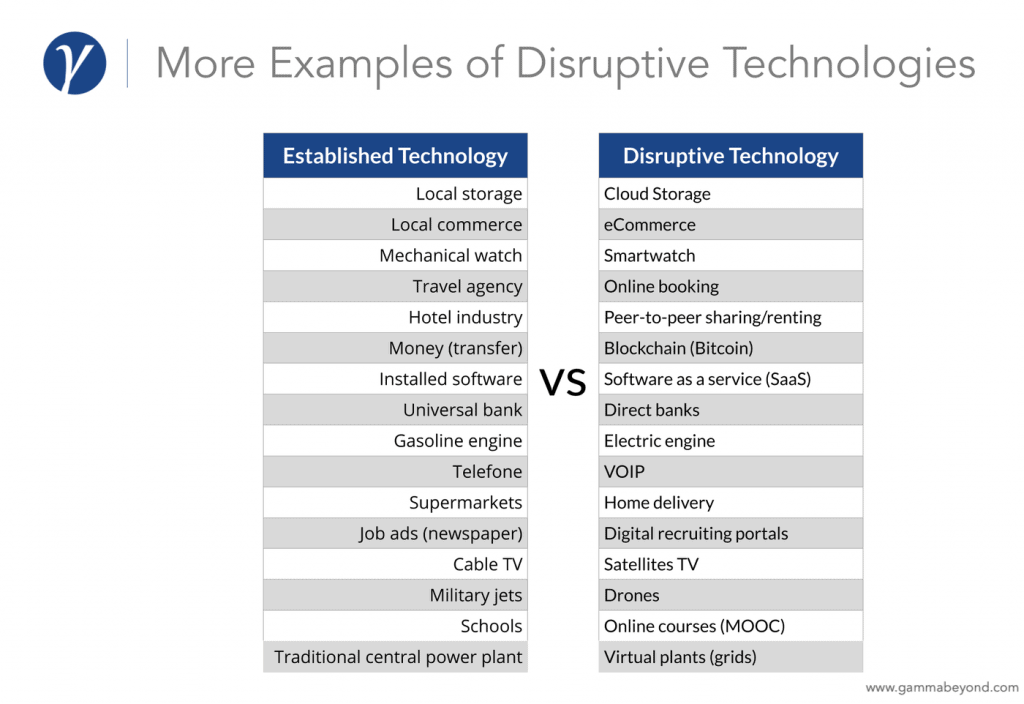

The examples are almost endless - from hydraulic shovels disrupting cable-winch shovels (in the early 20th century), PCs disrupting mainframes computers, online streaming disrupting retail movie rentals, inkjet printers disrupting laser printers or the Nintendo Wii disrupting the Playstation and the Xbox.

Then why do incumbents get stuck in this dilemma time and time again, even though history has repeated itself countless times?

Because companies do not (fully) understand or consider the principles of the Innovator’s Dilemma. Hell, most innovation and business consultancies don’t even understand that most disruption originates from incremental innovations (or think Uber is disruptive). And that’s even worse - they should know better and get for paid for it, because they tend to throw around the term like there’s no tomorrow.

3.1 Understanding Bad Habits

It’s crucial to understand how disruption occurs to grasp the seemingly “irrational”, recurring behavior and mindset of disrupted incumbents. I will do this by citing another example, this time from the steel industry - an industry I have had the pleasure working with extensively, as I’ve helped companies such as Kloeckner Metals define their strategy and develop ways to disrupt their own industry.

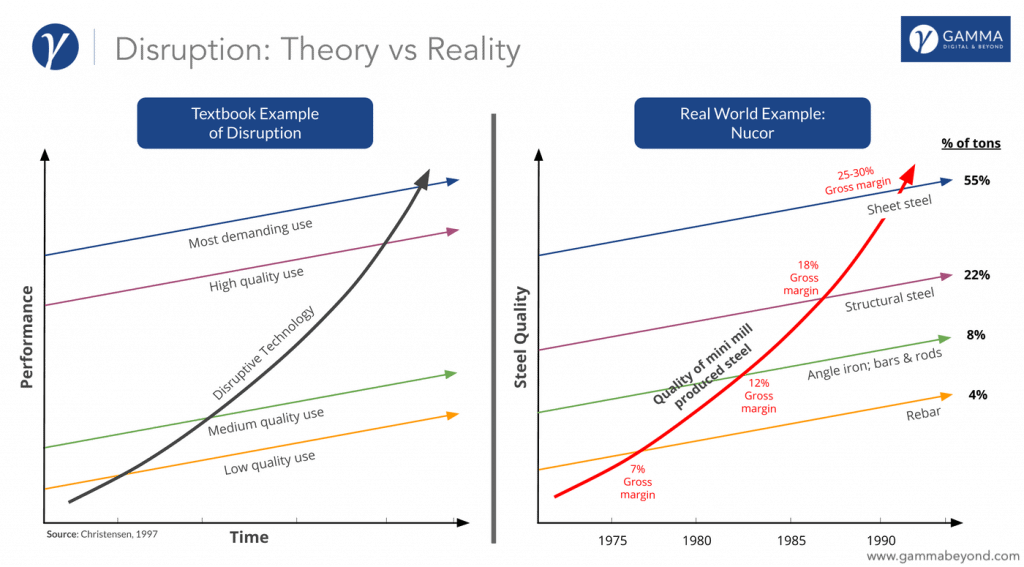

We will take a look at the disruption that took place in the steel industry from 1965-1990s and then elaborate, by dissecting this example, illustrating how and why disruption can happen.

3.2 The Rise of the Mini Mills

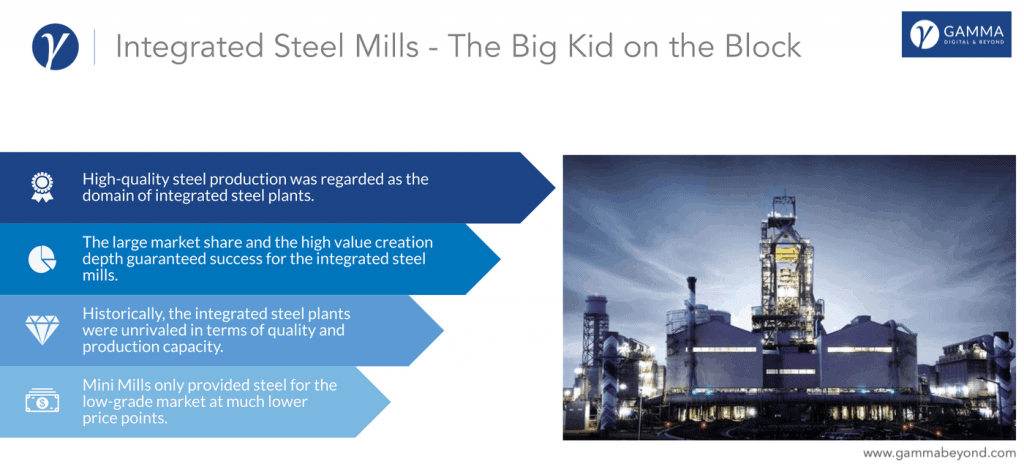

Enter the Integrated Steel Mills…

Historically, high-quality steel production was regarded as the domain of incumbents, the integrated steel plants, and were unrivalled in terms of quality and production capacity. Their large market share and high added value guaranteed success.

But in the mid-1960s mini mill steelmaking started to become commercially viable. Mini mills, pioneered by Nucor, employed widely available technology and equipment, using electric arc furnaces to melt scrap steel (as opposed to blast furnaces to melt iron) and then roll these into end products such as bars, rods, beams or sheets.15 And even though the integrated mills and mini mills look very similar, scale is the only differentiating factor. Mini mills use furnaces that are roughly 20 meters in diameter and 10 meters high, which is where they get their name from.

It costs approx. $8B USD to build a competitive integrated steel mill requiring the output to be much greater than that of mini mills. In contrast, mini mills can be built for much less and can produce steel at a fraction (less than 1/10th to be exact) of that of an integrated mills, making mini mill steelmaking a highly disruptive technology.

One would think that every integrated steel company would have adopted the low-cost mini mill technology, especially since steel is a commodity. Yet not a single integrated steel company had invested in a mini mills even after the technology occupied nearly half of North America’s steel production in 2000.

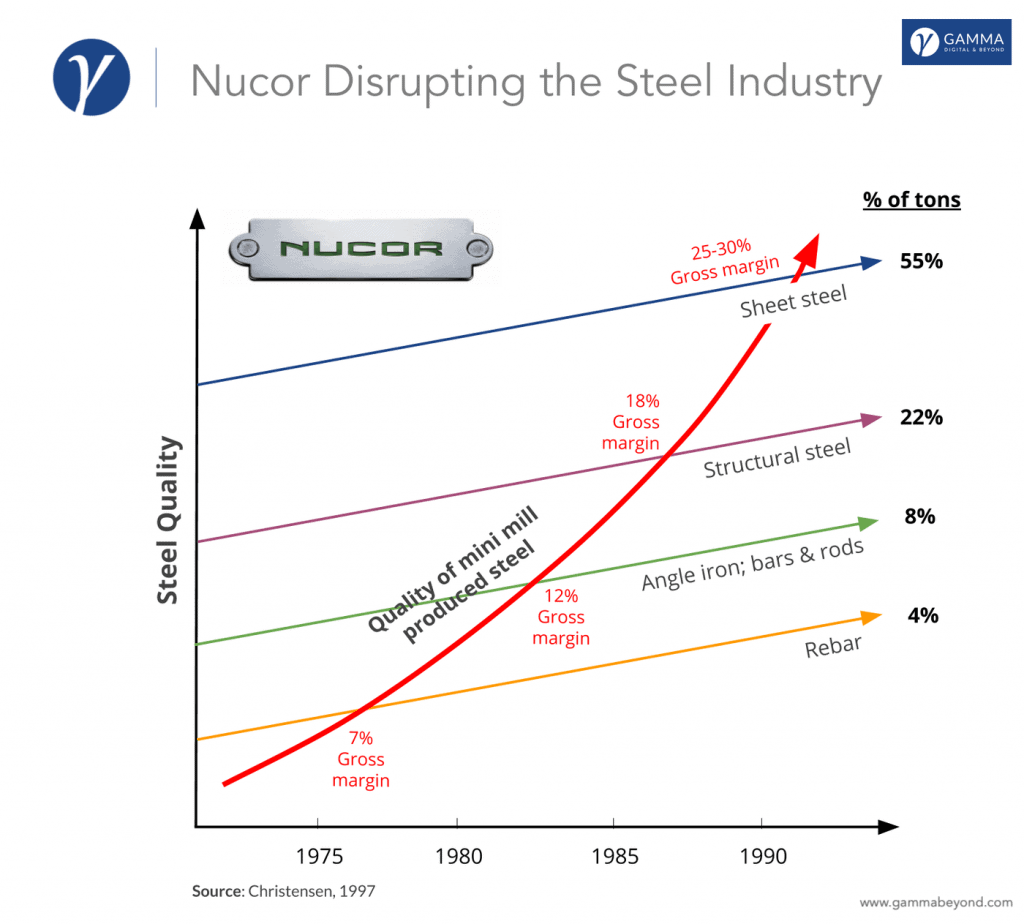

However, when mini mills first emerged in the ‘60s it used scrap steel, producing low-quality steel. So the only market mini mills could sell their product to was that of concrete reinforcing bars16 (rebars for short) - right at the low-end of the market in terms of quality, cost and margins (~7%). This market accounted for only 4% of the industry’s tonnage (see illustration below) and was also the least attractive for the integrated mills, as customers tended to be the least loyal. Customers would switch suppliers to whoever offered the lowest price. Therefore, integrated steel mills were more than happy to get rid of their rebar business.

As the disruptor captured more of the rebar market, they continuously improved the quality and consistency of their products and provided a wider range of metal shapes. This in turn enabled mini mills to attack the next larger market above them - angle iron, bars and rods (see chart). And again, the integrated mills we relieved to surrender this market to the disruptor.

Mini mills continued to move up-market, while integrated steel mills receded into higher margin markets, dramatically improving their balance sheets as they left behind their lowest-margin products.

By now, the only safe haven for the integrated steel makers was the sheet metal market, where quality-sensitive manufacturers of cars and appliances paid a premium for high-quality steel that were free of defects. This market was also protected from mini mill competition, because it cost around $2B USD17 to build a competitive sheet steel rolling mill - simply too much for even the largest mini mills.

While integrated mills were enjoying their profits and comeback, the German equipment manufacturer Schloemann-Siemag AG, introduced another disruptive technology in 1987, called “continuous thin-slab casting”. It allowed steel to be continuously cast from its molten state into long, thin slabs that could then be transported directly, without cooling, into a rolling mill. Moreover, such mills could be built for less than $250M USD, 1/10th the cost of a traditional sheet mill, well within the reach of mini mills, promising at least a 20% cost reduction for sheet steel.

Due to its huge advantages, every major player in the steel industry carefully evaluated its use in their respective mills. Ultimately, the integrated steel mills decided they couldn’t justify the cost, because thin-slab casting technology, when it first emerged, could not offer the high-quality and defect-free surface required by the integrated mills’ mainstream customers (carmakers and appliances). Furthermore, the technology was positioned in the least-profitable, most price-competitive and commodity-like end of their business and the integrated mills were busy competing with each other in the sheet market.

Guess who adopted the technology anyway? Again, Nucor paved the way and moved to last and only market occupied by the integrated mills.

…all was good...until the 1990s.

In the early 1990s the integrated steel mills could no longer compete with the superior cost and productivity advantages of the mini mills and most integrated mills went bankrupt. Ironically, history is already repeating itself with the so-called "Micro Mills" in the aluminum industry. Déjà vu, anyone?

3.3 How a Disruptive Predator Finds Its Next Lunch

As we’ve just seen from the mini mill example, disruptive innovation usually starts out with a low-quality product (i.e. rebar, also see chart above) in a low-volume and/or low-margin segment (i.e. construction) of a much larger and more mature market. The customers of this “lower” segment demand product attributes that mainstream customers (i.e. sheet metal) do not and are willing to give up performance. Or simply put, the disruptive innovation is not good enough for mainstream customers. More so, mainstream customers straight out reject the disruptive innovation, holding the incumbent hostage of its own success.

Because mini mill technology was inferior in the beginning, it could not provide all the higher quality steel products as could the integrated steel mills. In this stage new technologies18 can either be inefficient and seem more expensive, due to the fact that technologies have not yet scaled, or seem cheaper because they simply do less.19

The reaction from the incumbent also follows a predictable pattern (see chart below) - it is generally one of denial20. Furthermore, the incumbent is forced to ignore the new technology, as it is often a market segment of low interest (i.e. low-volume/low-margin) and does not meet the growth requirements dictated by its much larger company size. As such, the integrated steel mills exited the rebar market (remember it only accounted for 4% of the total market in tons) and left it for the mini mills to feast on.

As time went on, the mini mills occupied the rebar segment and started growing rapidly, solving their initial quality problems while retaining their cost advantage. This is normally where the disruptor goes through a rapid learning curve, solving further quality/performance issues and suddenly starts threatening the incumbent in its main markets e.g. angle, bars and rods.

The integrated steel mills scrambled to put together a response. But almost always this fails, as so in this case, because of the disruptor’s head start and culture that is much more adaptable (read agile) and retreats to a higher-end market e.g. structural steel.

Ultimately, the market begins to demand the replacement of the incumbent technology with the new technology. At this point, the whole market begins to see the potential and capabilities of the new technology, forcing the incumbent further up-market (e.g. sheet steel) and into a dead end with no market left to go to.

It’s important to reiterate: Disruption has little to do with technology or digital business models per se. That's why companies shouldn't focus on the digital part of the digital transformation “movement” as they tend to do in Germany. But unfortunately, this point is lost on most companies.

3.4 What Enables Disruption In the First Place

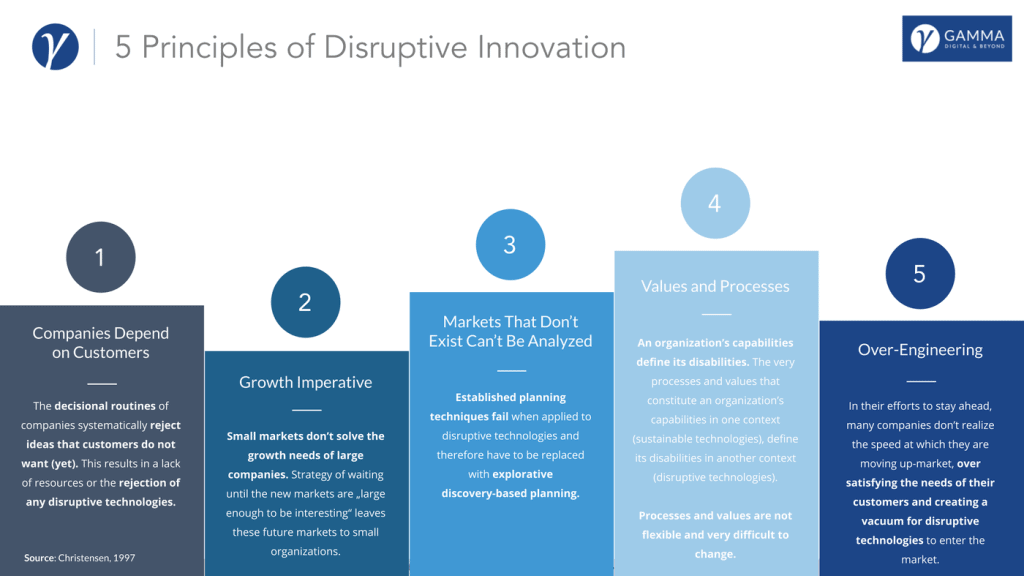

Christensen identifies 5 principles of disruptive innovation in his book that helps explain some of the reasons why incumbents get disrupted. I’ve already mentioned a few of them in the previous section, but let me explain each of them briefly (for a summary, see illustration below).

The 5 Principles of Disruptive Innovation

Companies Depend on Customers

The decisional routines of companies systematically reject ideas that customers do not want (yet).

Successful, well-managed companies are highly optimized in terms of listening to their main markets and investors keeping a watchful eye on its performance in those markets. So when a company pursues an activity that is relevant to its mainstream customers, it is rewarded by both customers and investors. When it pursues an activity that is irrelevant to mainstream customers (or even worse, causes a temporary reduction in profits), it is punished for getting “distracted”.

Just ask yourself: Would you sell more of the same or less of something with an uncertain future if parts of your salary depended on it? This problem is amplified even further when employees receive incentive stock options (ISO). It’s the economic equivalent to the tyranny of majority rule. The end result is a lack of resources and/or the rejection of any disruptive technologies.

Values and Processes

An organization’s capabilities define its disabilities.

When managers try to innovate, they generally assign employees within the organization that are capable to solve the problem. But at the same time these managers falsely assume that the organization in which they’ll work in will be just as capable at solving the problem. This means that organizations have capabilities that exist independently of the employees who work within them.

An organization’s capabilities reside in two main areas - its processes and the organization’s values. Processes as essentially the methods by which employees transform inputs such as labor, materials, information etc. into outputs of higher value e.g. high-quality sheet metal. The organization’s values are the criteria that managers and employees in the organization use when making prioritization decisions (e.g. How do we want to invest our money?).

Employees are quite flexible, in that they can be trained to work for a large corporation or for a small startup. Processes and values on the other hand, are not as flexible as people and very difficult to change. A process that is effective at producing paperback books, would be ineffective at producing e-ink readers. The same applies for values. Employees cannot simultaneously prioritize high-margin products and low-margin products. The very processes and values that constitute an organization’s capabilities in one context (sustaining technologies), define its disabilities in another context (disruptive technologies).

“They can neither withdraw from their profitable core business nor are they able to assert themselves in small, emerging markets with uncertain prospects for success due to their processes and structures.”

— Clayton M. Christensen

Markets That Don’t Exist Can’t Be Analyzed

Conducting market research or gathering data with old techniques when there is no existing market is almost impossible. For this reason established planning techniques fail when applied to disruptive technologies and therefore have to be replaced with explorative discovery-based planning.

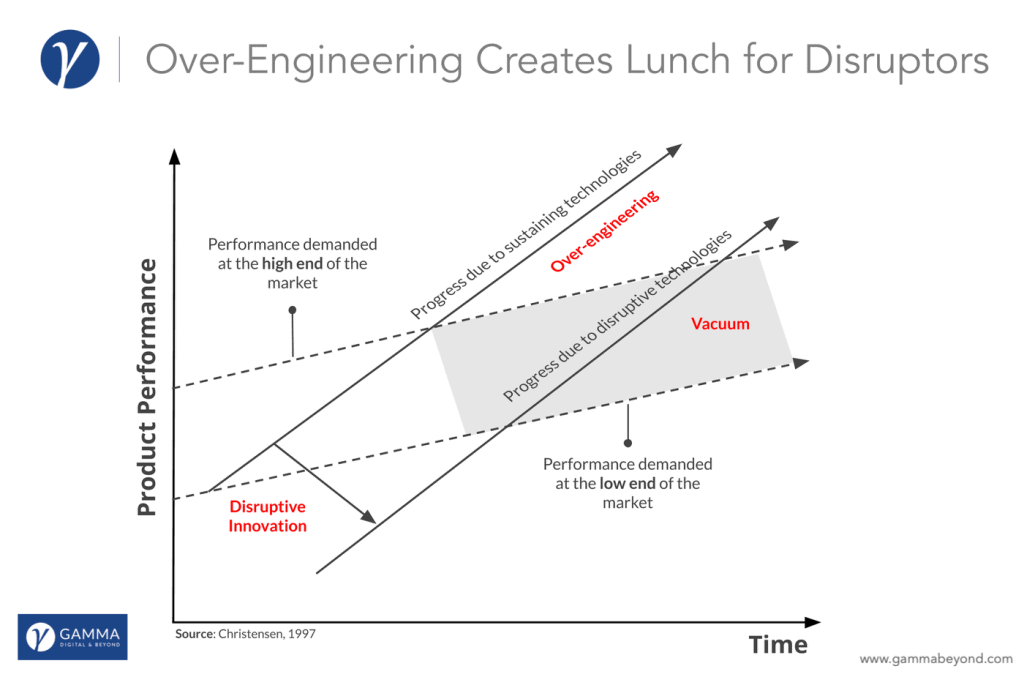

Over-Engineering

In their efforts to stay ahead, many companies don’t realize the speed at which they are moving up-market, over-satisfying the needs of their customers, by sustaining innovation and creating a vacuum for disruptive technologies to enter the market (see illustration below).

With the advantage of sustaining innovation it’s hard to go wrong. By either reducing costs or improving the product there is nothing major that can happen. In the worst case the customers won’t buy the product while in the best case there are (large) increases in sales.

Growth Imperative

Small markets don’t solve the growth needs of large companies.

Generally, the larger and more successful a company becomes, the harder it is for them to enter or create a disruptive market/product. It’s simple math: To grow 10% per year for a small company (e.g. $3M USD) is much easier than for $3B USD company, requiring a whopping $300M (instead of $300K) in new growth.

The common strategy of waiting until the new markets or disruptors are „large enough to be interesting or bought“ leaves these future markets to small organizations (disruptors). And this happens more often than you think!

Blockbuster's CEO once passed up a chance to buy Netflix for only $50 million - pocket change for Blockbuster at the time. Back in 2000, Reed Hastings, CEO of Netflix, approached former Blockbuster CEO John Antioco and offered to sell his company for said amount. Antioco ended up declining the offer, because he thought Netflix was a “very small niche business”.

A similar scenario played out in Germany when Bertelsmann was debating of buying Amazon, but ultimately decided to wait until Amazon was big enough. Today, Amazon is definitely big enough, but probably too expensive for Bertelsmann to buy. Talk about regret…

3.5 How German SMEs Respond to Disruption

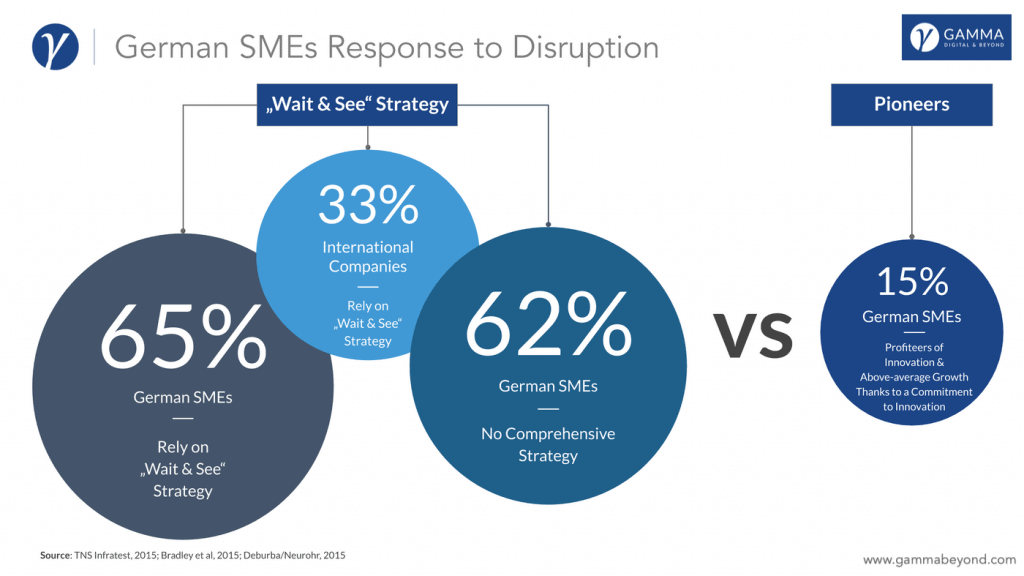

If we now take a quick look at how German SMEs, with arguably the most highly specialized market leaders in the world, respond to disruption, we can clearly see one thing: it’s mostly inadequate.

Almost 2/3 of the German SMEs rely on the “Wait & See” (if we get disrupted) strategy and have no comprehensive strategy in place. I guess they took the wrong page out of Bertelsmann’s playbook. Internationally it’s not quite as bleak, where 1/3 of the international companies rely on the “Wait & See” strategy.

Not even 1/5 of all SMEs are considered “pioneers”, profiting from an above-average growth thanks to their strong commitment to innovation.

3.6 Why Doing the Right Thing Is Hard to Sell

To illustrate why it's so hard to convince executives to do the right thing, let’s envision a discussion with an employee (let’s say he's a VP of Innovation), one that not only understands disruptive innovation, but also understands the underlying principles and her rational CEO.

VP: Hey, we need to start disrupting ourselves by allocating large chunks of our resources and money to an upcoming technology to secure our companies’ future.

CEO: Sounds intriguing! How does the performance stake up against our current product? And what margins are we talking about?

VP: Well…even though it currently performs worse than our current product and has considerably lower margins, it does show a lot of promise. I’m confident that as the technology improves over the next few years, it will be somewhere on par with our current offering.

CEO: Uhm…OK? Do you at least have any of our mainstream customers that are willing to buy this new technology of yours? Tell me, how big is the market?

VP: Not really, very few customers of these customers want it. But we did identify a small group of customers that are interested in the product, despite its low performance. The market size is presently very small, almost negligible. We estimate about $2-3M USD.

CEO: And I’m supposed to say YES to this crazy proposal? What the hell did you smoke?! You are hanging around Elon too much!21 Who in their right mind would invest in such a lackluster idea? Are you aware that our current product is having its largest earnings this year with a YOY growth rate of 50%? We’re currently investing all our R&D resources to expand into higher margin products. You're lucky I don't fire your a**!

At this point we all know what the employee should answer by screaming something like this:

Now, imagine the same scenario where the CEO is trying to sell this idea to his or her shareholders - a scenario with arguably higher stakes. Remember? The group of people responsible for the CEO bonus. Hardly any employee or CEO would have the balls to make that kind of suggestion, unless you’re Amazon of course. But that’s baked into their DNA from the start and this risk-taking is generally accepted by Amazon shareholders.

Despite this being a fictional scenario (I promise!), which is obviously exaggerated for illustration purposes, it still drives home an important point:

Even if you understand what needs to be done and why, it still doesn’t make it any easier to sell this “irrational” plan to the people in charge.

This phenomenon coincidentally has a name and it’s called “resource dependence theory”. Don’t worry about the fancy academic jargon, I’ll explain it in simple terms.

Most CEOs would certainly believe that they’re in charge of their company and that they are also the ones that make all the key decisions, which are then executed by its employees. But in reality it’s the customers who essentially control what the company can and cannot do. Now before you give yourself a facepalm and think: “Duh, that’s obvious! Why are you telling me this - of course the customer is ultimately in charge!”, let me elaborate, as this has huge implications.

An organization's freedom is dependent on satisfying the needs of those entities outside the company (i.e. customers, investors etc.) that provide it with resources it needs to survive. If this sounds like something out of biology class, you’re actually spot on. The concept of resource dependence is heavily based on biological evolution, that states that organizations will only survive and grow if their employees and systems serve the needs of their entities (customers and investors) by providing them with the products, services and profit they require. Organizations that do not will die, being starved of the revenue they need to survive.

Following this logic, Darwin’s evolutionary principle “survival-of-the-fittest” makes sure that companies that succeed in their respective industries are generally those whose people and processes are most focused on providing their customers with what they want.

So even if your visionary CEO wants to take the company in a completely new direction (say build a mini mill for example), the power of the customer-focused employees and processes and the highly-evolved survival mechanism in its competitive environment will reject the CEOs new direction. And because these forces outside the organization provide the resources that the company is dependent on, it is the customers (not the CEO), who really determine the direction the company takes.

Now think about that for a second and what it actually implies!

For those of us who are managing companies (or have in the past) or are in management consulting, this is a rather depressing thought. We are all there to make a change, implement a strategy or to improve profits. However, resource dependence contradicts the very reason for existing. What’s even more disheartening is the fact that there is overwhelming evidence that the customer-focused resource allocation and decision-making processes of successful companies are far more powerful in directing resources than are executives’ decisions.22

Then what should managers do when faced with disruptive technology when its company’s customers reject this very technology?

We will answer this question by examining how a successful startup from Berlin disrupted an entire industry within just a few years - this time from the perspective of a disruptor.

Key Takeaways

- Because companies do not fully embrace the powerful principles of the Innovator’s Dilemma, incumbents regularly get disrupted in a predictable fashion - simply for doing everything right.

- Ironically, the companies respond in a very rational manner.

- Customers essentially hold companies hostage for being successful, demanding further improvements to its products and services for which they are willing to pay higher prices.

- Mainstream customers tend to reject disruptive technology.

- As companies retreat into more lucrative markets, it leads incumbents into a dead end with no escape.

- Only if an organization satisfies the demands of its external stakeholders, can it further exist, as these entities provide it with the resources it needs to survive.

- The highly-evolved customer-focused employees and processes within a company will outstrip the decision-making power of executive when it comes to resource-allocation.

4. How a Small Startup with No Prior Experience Disrupted the Entire Heating Market within Just a Few Years

Enter Thermondo…

When startup Thermondo first entered the market, they wanted to help German SMEs become self-sufficient with all their energy needs. But they soon realized that their B2B business model was not viable for such a small startup. After discovering that in every developed country the residential heating market was an underserved segment, they rapidly pivoted to become the Immobilienscout (or Zillow for English-speaking readers) for this market and developed a B2C marketplace to bring transparency to an otherwise very fragmented market. Thermondo, as an in-house heating service provider, offered tailored heating systems for a fixed price without the need for on-site appointments and inventory. (With the competition, customers would often have to take off from work just for the initial on-site visit - a huge pain for most customers).

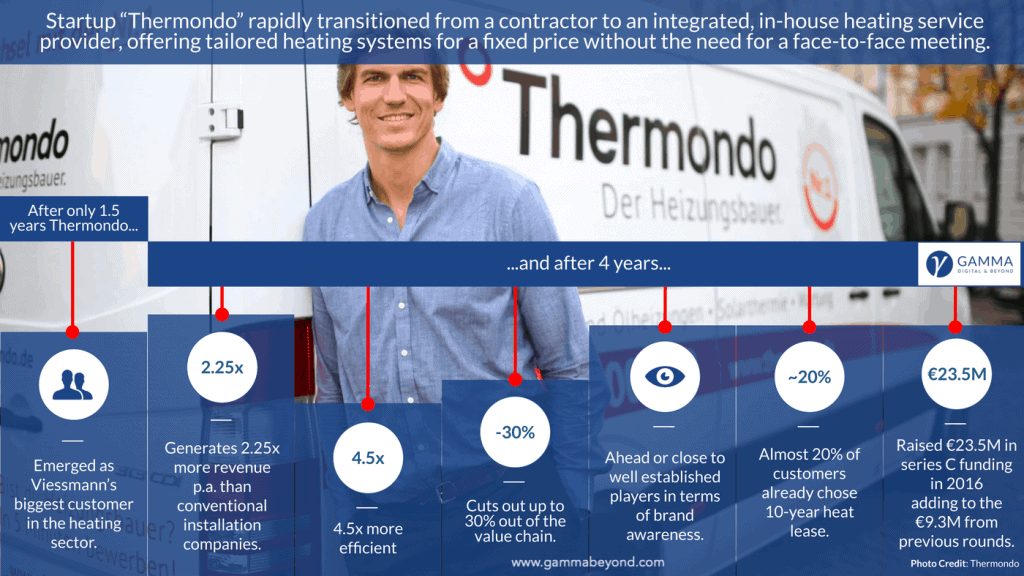

Today, Thermondo is Germany’s largest heating installer and among the top 5 fastest growing startups in Germany, generating 2.25x more revenue per year than conventional installation companies, while being 4.5 times more efficient.

How were established players in the residential heating market blindsided by a startup with no prior industry knowledge?

In order to understand how they managed this feat, we need to look at the retrofit heating market before 2012.

4.1 The Residential Heating Market Before 2012

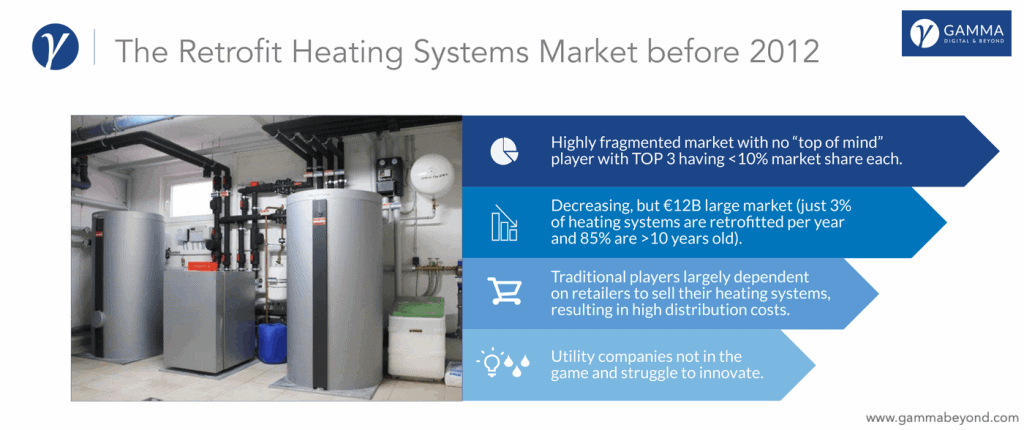

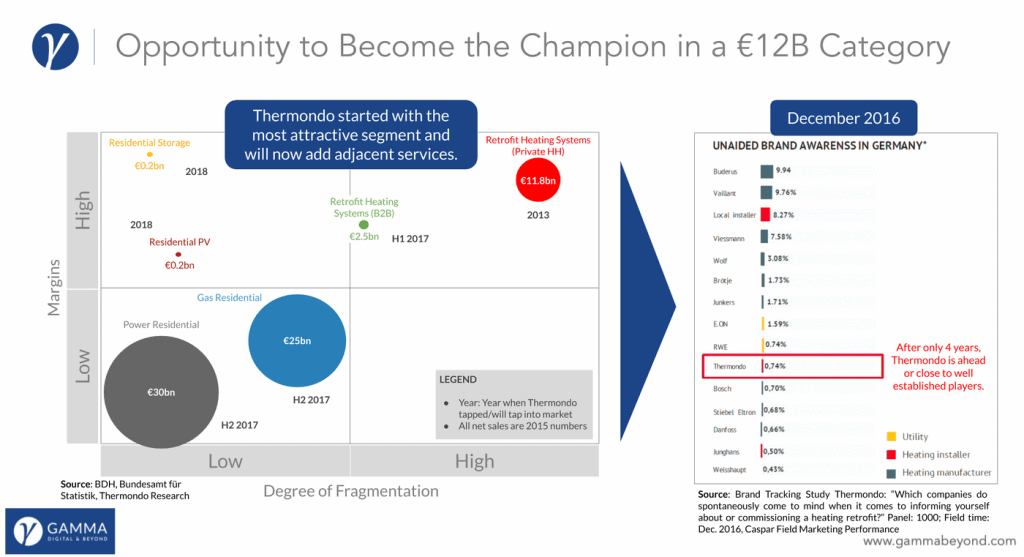

The residential heating segment was a decreasing, albeit a €12B EUR large market with just 3% of the heating systems being retrofitted every year, 85% of which were >10 years old. (Just think how often you replace the heating system in your home with a more modern and efficient one.)

Historically, the market had been highly fragmented with no clear “top of mind” player. Each of the top 3 manufacturers had less than 10% market share. Traditional players such as Buderus, Vaillant or Viessmann were largely dependent on retailers to sell their heating systems, resulting in high distribution costs. Utility companies on the other hand, were not even in the game and struggled to innovate.

4.2 On a Path to Disruption

When Thermondo launched its first product, a B2C marketplace in 2013, they aggregated customer demand and contracted various manufacturers and partners to install heating systems for their customers (home owners), essentially becoming an online broker for heating systems. After the launch, however, it turned out that the partners Thermondo contracted to carry out the installations on behalf of their clients, were not as diligent and reliable as they had hoped. For Thermondo, to whom customer satisfaction is one of the top priorities, this was simply unacceptable. The only logical consequence for them was to pivot again and hire installers themselves.23 And with this move, they became an end-to-end service provider owning the customer relationship and the install base (customers).

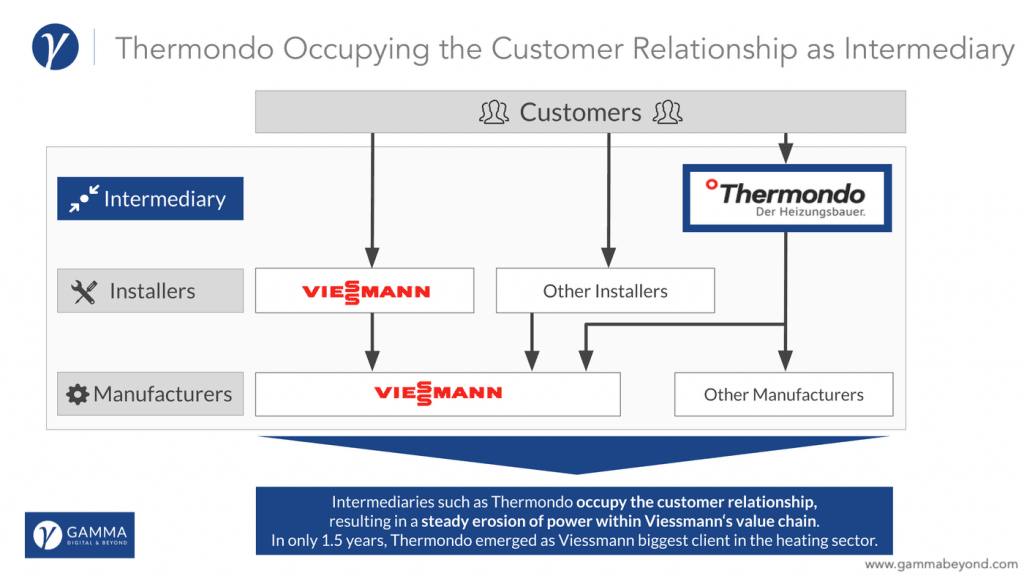

After only 1.5 years Thermondo emerged as Viessmann’s biggest customer in the heating sector, by occupying the customer relationships between manufacturers (e.g. Viessmann) and installers, which lead to a steady erosion of power within Viessmann‘s value chain. As you can imagine, this was a major wakeup call for Viessmann and they quickly scrambled to put together a response.24

And after 4 years, Thermondo’s learning curve continued to rapidly improve, as they generated more than double the revenue of their competitors, eliminating up to 30% out of the value chain. And by utilizing intelligent algorithms it also allowed Thermondo to be 4.5x more efficient. By the end of 2016 they were ahead or close to well established players in terms of brand awareness.

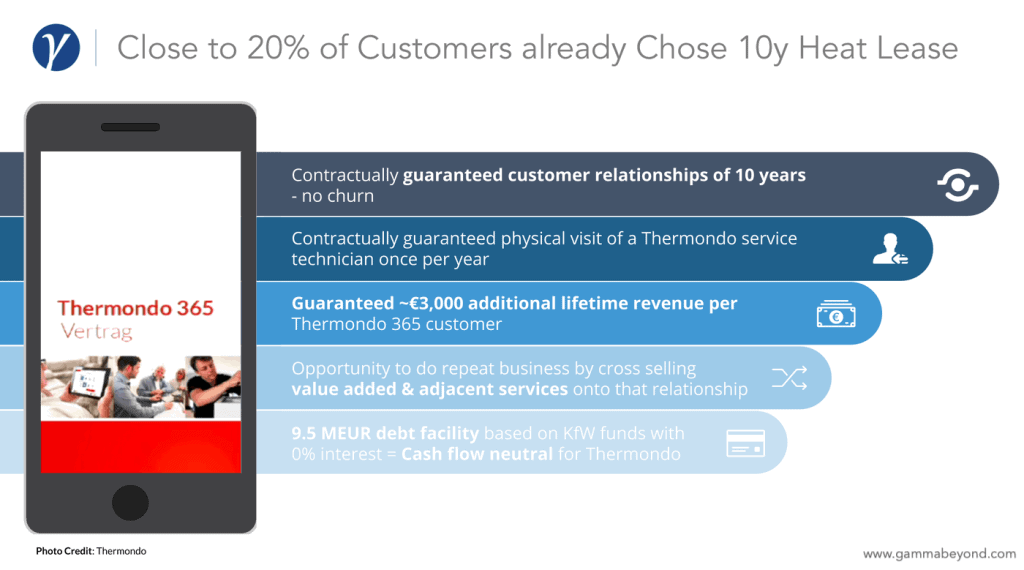

In 2016 they also introduced “Thermondo365”, a full-service and managed heating lease for homeowners with no up-front costs.These leases are typically 10-year contracts with no churn, contractually guaranteeing Thermondo one physical visit per year and an additional ~€3,000 EUR lifetime revenue per Thermondo 365 customer. This provides Thermondo with an opportunity to do repeat business by cross selling value-added & adjacent services onto that relationship. They pre-finance the up-front costs for their customers by raising debt from KfW funds at a 0% interest rate, making it cash flow neutral for Thermondo.

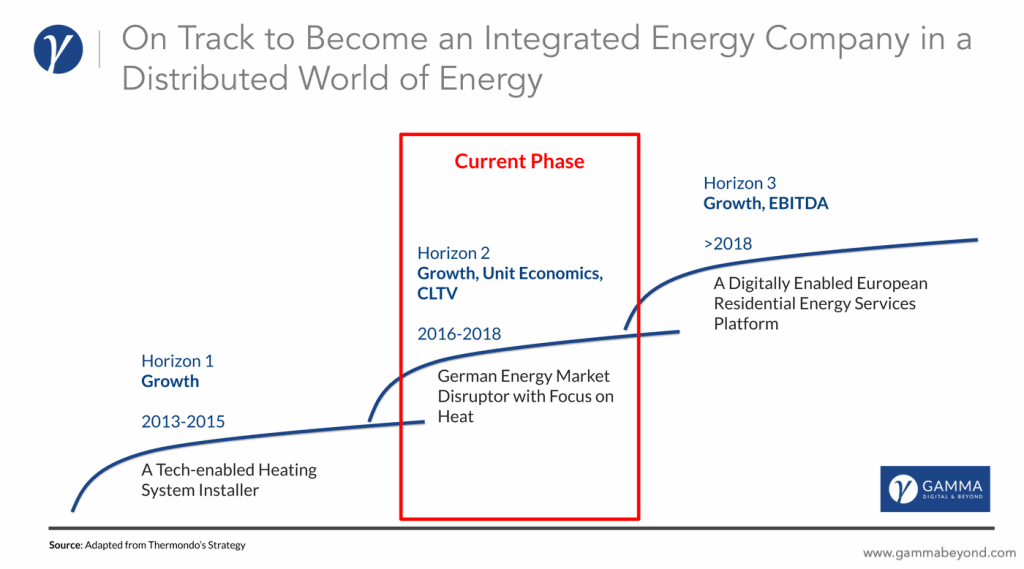

If we take a look at Thermondo’s strategy beyond 2018, we can see that they’re well on track to become an integrated energy company in a distributed world of energy.

4.3 Thermondo’s Road to Success

There are a few key learnings we can extract from Thermondo’s approach. Let’s go through each one briefly.

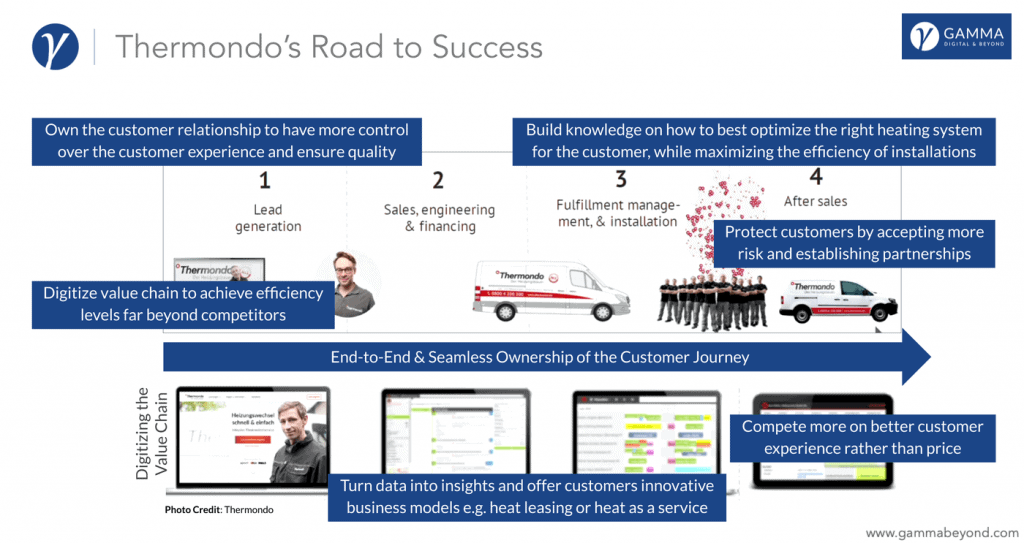

1. Own the customer relationship, end-to-end.

Ever since Thermondo decided to become installers themselves, they became an end-to-end service provider, owning the customer relationship and the install base. This enabled them to have more control over the customer journey, offering customers a seamless experience, while maintaining a high level of service.

If your company has multi-level sales and distribution channels (e.g. B2B2C), similar to STIHL, this can pose a serious threat. Oftentimes, your retailers and distribution partners tend to know much more about actual customer needs than your company, making the ownership of the relationship extremely difficult, if not impossible. Key point: Don’t let anyone else own your customer relationships.

2. Protect customers by accepting more risk.

By hiring and training installers themselves, Thermondo accepted more risk to improve the overall customer experience. And with their product Thermondo365 they even went a step further, assuming debt for their customers, by financing the upfront costs for the actual heating system. This strategy is similar to what AirBnB and Uber are currently doing - building their own hotels and buying their own cars.

3. Digitize the value chain to achieve efficiency levels far beyond competitors.

Growing and having this much success in such a short period isn’t possible by scaling at least part of your business model. For this reason Thermondo views itself as a technology-enabled heating provider, by harnessing software to support planning and training operations. This gives them a clear advantage in terms of efficiency, when compared to their competition. Where Thermondo’s competitors require 9 installers, they achieve the same results with two.

4. Build knowledge on how to best serve your customers, while maximizing efficiency.

Levering their experience from on-site customer visits and data analysis, Thermondo has a very good understanding of actual lead times, their current installation capacity, the radius of their teams, target dates for installation and therefore knows exactly when and how to generate a particular lead, all while keeping zero inventory.

They generate these insights by two custom-developed tools, one for lead generation and one for pricing, acting like an airline with dynamic pricing. In addition, they use two software engines - Manfred, a software algorithm, and Diego a project management suite for scheduling and planning. These tools allow them to scale and train their salespeople using software. The software also produces a bill of material, enabling Thermondo to be an inventory-free company, using just-in-time delivery.

Installers are equipped with Android tablets with an app for themselves and their customers, allowing Thermondo to tap into wholesale data using their ordering software and are immediately informed about hardware availability.

5. Turn data into insights and offer customers innovative business models

Thermondo clearly stands out for its use of intelligent algorithms, allowing them to offer different business models.By not having any inventory for example, Thermondo can offer various additional services that the competition cannot offer e.g. heat leasing or heat as a service (along with different business models).

6. Compete on better customer experience rather than price.

This point should be obvious, but important enough to reiterate. Instead of competing on price and going down the path of commoditization, Thermodo continued to add more and more value, improving the overall customer experience.

Key Takeaways

- Don’t be afraid to pivot (multiple times if need be) if you notice something isn’t working. Always be prepared to challenge and test your assumptions with real customers. Remember Mike Tyson’s quote: “Everybody has a plan until they get punched in the mouth”.

- Don’t let anyone own your customer relationships. Detaching yourself from actual customer needs is very bad organizational habit to keep.

- Being a disruptor means thinking in bold new ways. Therefore you can’t simply ask consumers what they're looking for. Disruptors such as Thermondo get to core needs and the jobs-to-be-done. Always focus on the problem the customer is facing, not the solution or features they're asking for. Or, as Ash Maurya said: “Love the problem, not the solution.”

- Be prepared to sacrifice growth in order to keep customer satisfaction high, especially during the early phases of launching your product or service.

5. How to Change Before Change Changes You

Equipped with all this knowledge, how does a company go about solving the now apparent dilemma?

I will highlight a few product and organizational strategies allowing you to embrace, rather than fight, disruption. We will start with product strategies, as these tend to be the most concrete, and then move on and outline organizational strategies required for becoming a disruptor. Finally, I will leave you with some practical tips on how to increase the changes of disruptive technology succeeding in your organization. These strategies and tips will help your company make the jump from one S-Curve to another. But keep in mind, this is by no means an exhaustive list.

5.1 Product Strategies to Increase Your Odds

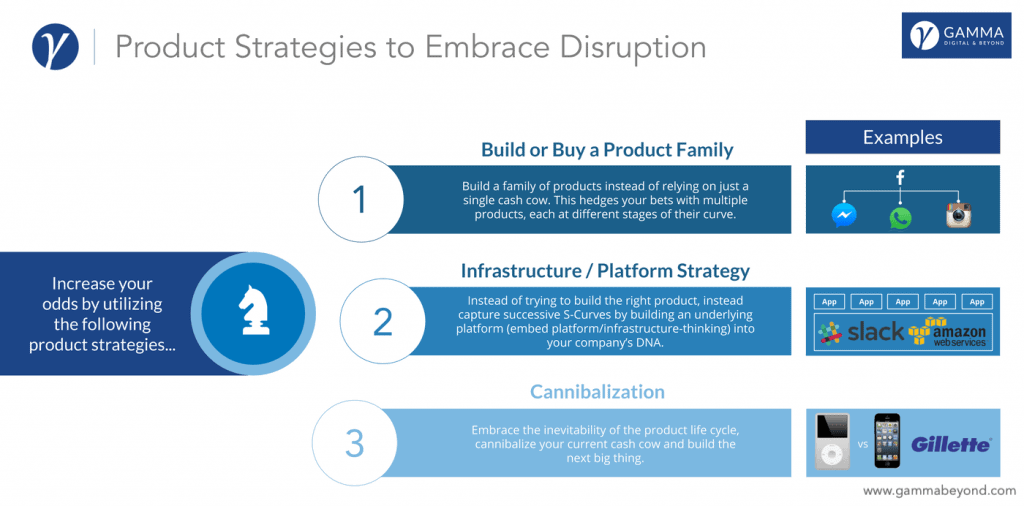

1. Build or Buy a Product Family

The first strategy is gambling. Well, kind of. It’s more like hedging your bets and increasing your odds of success, by building a family or portfolio of products instead of relying on a single (fat) cash cow. This can and should also include the potential acquisition (or cooperation) of startups that fit within this product family. Facebook is a good example with their family of service e.g. Instagram, Messenger and WhatsApp.

Amazon embodies this philosophy extremely well, by embracing an experimentation and failure mindset. A particular lengthy quote from Jeff Bezos summarizes this mantra of making multiple bets over time (emphasis mine):

”One of my jobs is to encourage people to be bold. It’s incredibly hard. Experiments are, by their very nature, prone to failure. A few big successes compensate for dozens and dozens of things that didn’t work. Bold bets — Amazon Web Services, Kindle, Amazon Prime— all of those things are examples of bold bets that did work, and they pay for a lot of experiments.

I’ve made billions of dollars of failures at Amazon.com. Literally, billions of dollars of failures. You might remember Pets.com or Kosmo.com. None of those things are fun. But they also don’t matter.

What really matters is, companies that don’t continue to experiment, companies that don’t embrace failure, they eventually get in a desperate position where the only thing they can do is a Hail Mary bet at the very end of their corporate existence. Whereas companies that are making bets all along, even big bets, prevail. I don’t believe in bet-the-company bets. That’s when you’re desperate. That’s the last thing you want to do.”

— Jeff Bezos

2. Invest into Platforms and/or Infrastructure

Amazon’s AWS is probably a prime example of this strategy. Their cloud infrastructure generates around $25.7B USD25 (11% of total revenues) for Amazon alone, with a profit margin of around 25%, hosting roughly 4.7%26 of all websites, including many businesses, governments, stock markets etc. 4.7% might not sound like much, but there are 1.8B hostnames and 178M websites. So if AWS as a whole ever goes down, that would prove to be very bleak day. And probably worst of all: Netflix would stop, thus proving the end of civilization for some.

Amazon also indirectly profits from any products and services that are built on top of their infrastructure, because over time, Amazon can develop new business models based on the use-cases of AWS customers.

3. Cannibalization

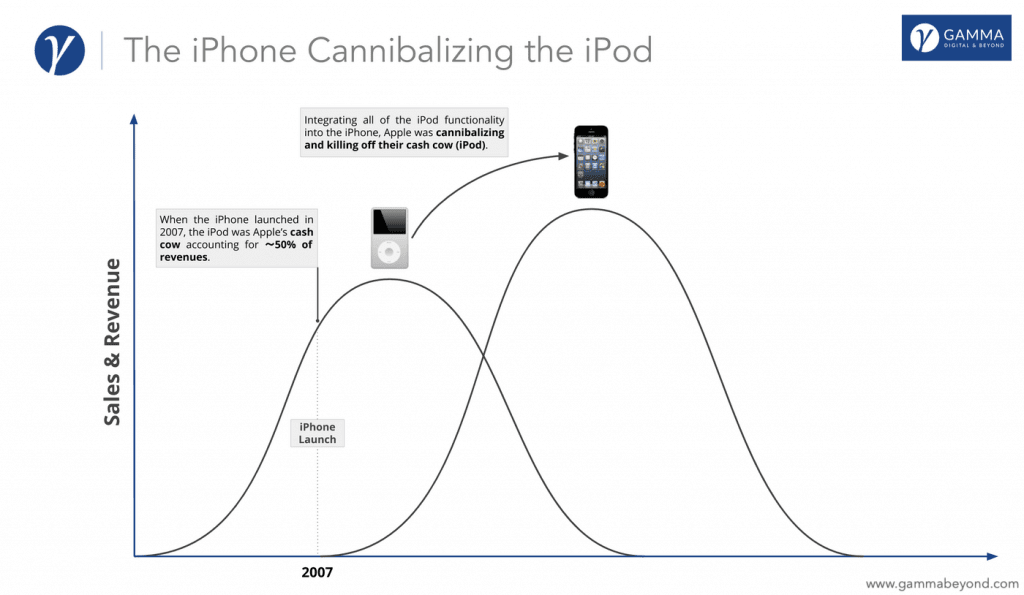

In 2007 when the iPhone launched, the iPod was Apple’s cash cow accounting for 〜50% of revenues. Integrating all of the iPod functionality into the iPhone, Apple was cannibalizing and killing off their cash cow - the iPod.

Apple’s core philosophy has always been to embrace the fact that customers generally care little about the past and to catch the next innovation S-Curve while you’re still on top. If that means cannibalizing your biggest cash cows, so be it. This is something Steve Jobs fully embraced, even mentioning Clayton M. Christensen’s concept in his biography.

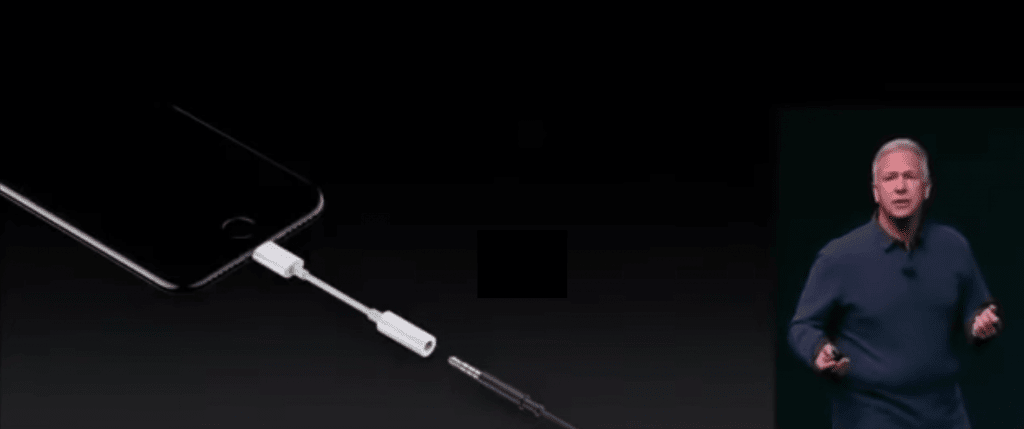

If Apple’s strategy was to sell more iPods or to focus purely on profit, it’s safe to assume that the iPhone may never have launched. Tim Cook reiterates this strategy nicely, by citing its own history of cannibalization, listing a few examples:

“Our core philosophy is to never fear cannibalization. If we don’t do it, someone else will. Macintosh killed the Apple II. We know that iPhone has cannibalized some of our iPod business. That doesn’t worry us. We know that iPad will cannibalize some Macs. But that’s not a concern.”

Most large companies wouldn’t take the risk and invest resources to develop and launch a product that is not nearly as profitable as their existing cash cow, let alone in a market that does not even exist. Companies simply cannot bring themselves to make decisions that would result in their cash cow being completely cannibalized. It just doesn’t make financial sense to create new products at the expense of your profitable products. But it’s exactly this fear that has left many great companies open to disruption.

How Gillette Cannibalized Itself

Gillette provides us with another great cannibalization example. A few years back the Mach3 Turbo was Gillette’s top-of-the-line, best-selling razor and hugely profitable. Just how profitable? Gillette’s manufacturing costs per razor is $0.10 USD, but their customers pay 48 times that amount in stores.27 Off the top of my head, I'm not sure if even cocaine has these profit margins. I’ll have to ask my non-existent dealer for more details next time I get a chance.

In any case, when the Fusion ProGlide was introduced, the marketing team at P&G made the deliberate choice to get old (not new) customers to purposely switch to the new product. P&G promoted its top-of-the-line Fusion ProGlide at the expense of its older Mach3 Turbo. This was a smart strategy and paid off.

Remember to keep this in perspective, both Fusion and Mach3 generate billion-dollars for P&G. As a comparison, this is what the author of this article makes in 5 years! 🙂 So to cannibalize your existing, billion-dollar product takes…how did Apple put it, when they got rid of the headphone jack on the iPhone 7? YES, courage! That’s what it takes.

Original Video Clip: here

By now, the Dollar Shave Club28 and other startups have started disrupting this very industry and it will be an interesting thing to watch. Maybe even another disruption case we can learn from.

5.2 Organizational Strategies to Embrace Disruptive Technologies

1. Creating a Separate Unit Independent of Your Legacy Organization to Kick Start Innovation

When faced with disruption, a companies’ management generally has two choices:

A. Pick a fight with the very powerful tendency of organizations and external stakeholders that ultimately control the investment patterns of a company and mainstream customers outright rejecting disruptive technology.

B. Harness, rather than fight its power, by creating a separate independent organization with its own set of resources, processes and core values.

Time and time again, incumbents believe they can defend against a disruptive attack by choosing the first option. This attitude is partially prevalent among German SMEs. How dangerous this mindset can be, is illustrated by a study conducted by Tevitz in 2013 that revealed the following:

- Only 9% of the researched incumbents recover from a disruptive attack.

- Out of these successful companies, all of them have founded separate units to master disruptive technologies.

- Not a single company with an integrated approach was able to successfully fend off the disruptive attack.

Companies facing existential threats often feel the need to try some sort of major transformation, using change processes that worked in the past and hoping the outcome will be successful once again. But the old ways of implementing strategies are failing them more and more. It’s like trying to retrain an elephant so that it can become both an elephant and a cheetah. When has that ever worked? Then why are established companies so reluctant to create a separate unit outside of their legacy organization?

Only independent organizational units can successfully develop disruptive innovations, because incumbents need a way to respond to disruption as it’s occurring. These units must be matched to the size of the target market in order to be able to quickly act and adapt within smaller markets, while the core business continues to manage large markets to meet its associated growth requirements. As companies grow, they naturally lose the ability to enter small emerging markets.

If executives would stop using a “one-process“ and “one-organization-size”-fits-all” approach for all types of innovations, they would greatly improve the chances of new ventures succeeding.

Likewise, first-mover advantages are essential in emerging markets with disruptive technologies.29 But this doesn’t mean companies should panic and dismantle their still-profitable business. Instead, their legacy organization should continue to nurture and strengthen its relationships with its core customers, by continuing to invest in sustaining innovations. The new division can then focus solely on the growth opportunities that arise from disruptive technologies and players.

Research strongly suggests that the rate of success of independent units depends largely on keeping them separate from the core business. And yes, this means that incumbents will have to manage two very different operations for the time being.

Be sure to create and celebrate any visible significant quick-wins (e.g. lighthouse projects) that originate from the separate innovation unit. Otherwise skeptics will throw obstacles in your way, unless they see proof that this “foreign object” is actually making an impact. And people have only so much patience, so you must move with a sense of purpose and urgency.

It’s also very important to create a safe space for your initial ideas, otherwise skeptics will be swift to destroy any new ideas and motivation that the separate division has.

One very big mistake to avoid, when creating such a division:

Do not have the unit depend on a budget for which it has to seek approval from the core business. This will almost certainly crossfire. How likely do you think it will be that this independent unit will develop disruptive technologies that undermine the core business of its legacy organization from which it receives its annual budget? Even animals know not to bite the hand that feeds them (also refer to resource dependence theory).

Creating a separate and independent unit by itself will not be enough to change the tides, even if your company already has a “super special autonomous innovation team”. Often, these teams are made too autonomous, while the legacy organization continues to operate in its siloed, habitual fashion. Innovation units, on the other hand, are often doing their “blue-sky thinking” without an immediate effect on the company’s bottom-line. And that’s OK for the short-term, but at some point in the foreseeable future both legacy organization and innovation unit need to be able to interact freely across hierarchies and departments in order to think about and question major challenges in the context of daily business. This is where following strategy comes into play.

"When people shake their heads because we are living in a

restless age, ask them how they would like to life in a

stationary one, and do without change."

— George Bernard Shaw

2. Establishing a Second Operating System That Operates in a Congruous Manner

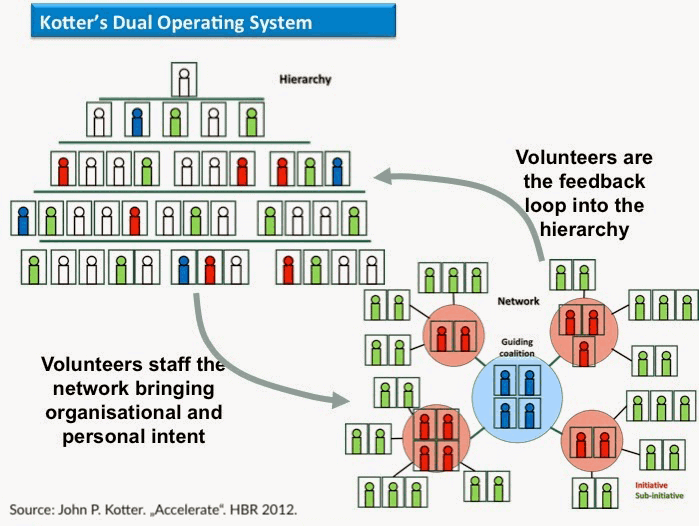

Once your innovation unit has demonstrated to the legacy organization that it can make a significant impact, by delivering actual results to its core business, you’ll need to make both organizations work together. This should be your long-term objective. To achieve this, John P. Kotter’s concept of a dual operating system for organizations has proven to be very effective and successful.

Traditional organizations with its hierarchies and processes are an organization’s “operating system”, that excels at execution, delivery and efficiency. But this operating system is not structured for certain types of innovation and is too inflexible for the rapid changes in today’s environment.

Most startups have a 2nd operating system that has an agile, network-like structure with its own set of processes. It enables them to continually adapt to the business, the market and the organization, by reacting with greater agility, speed, and creativity than the existing one. After all, startups need to stay lean and creative in order to quickly seize opportunities.

These two operating systems work in concert with each other, combining the entrepreneurial capability of a network with the organizational efficiency of a traditional hierarchy.Both are connected to and coordinated with the hierarchy in various ways, primarily through the people who occupy both systems. Rather than overwhelming the traditional hierarchy, it frees the latter to do what it does best. It also coincidentally makes the whole company easier to manage and accelerate the much needed change.

Employees of the 2nd operating system set their own goals and decide themselves how they operate - it’s not a top-down approach! You cannot simply define top management objectives and expect your employees to be excited about them. Instead, it’s the voluntary participation that will determine the objectives. However, they all work within the guard rails that have been defined by top management. That makes them feel confident enough to go out and do the necessary work.

An excellent example of this approach is P3 Group, a company with over 3,900 employees across 40 different locations. Instead of a traditional hierarchy, P3 employs a network structure throughout all its locations where subsidiaries govern themselves, by deciding what knowledge they share and how they collaborate e.g. on an individual project basis or through a joint venture between subsidiaries.

The same applies for employees. And, as a natural consequence, P3 doesn’t have job descriptions for most employees, leading to overlapping hierarchy levels, and, in some cases ambiguous organizational structures (which they have no problem with). Employees are also allowed to select their own boss at any time, depending on what aspirations, motivations and skills they have or want to develop.

P3’s organization essentially evolves with the challenges of their customers. Rather than trying to solve new challenges with old organizational approaches, P3 is constantly evolving with these challenges, by adopting the most practical structures. At any given time, there’s always a part of P3 that is being re-organized.

3. Align or Reorganize Your Company to Have a Single Profit&Loss (P&L)

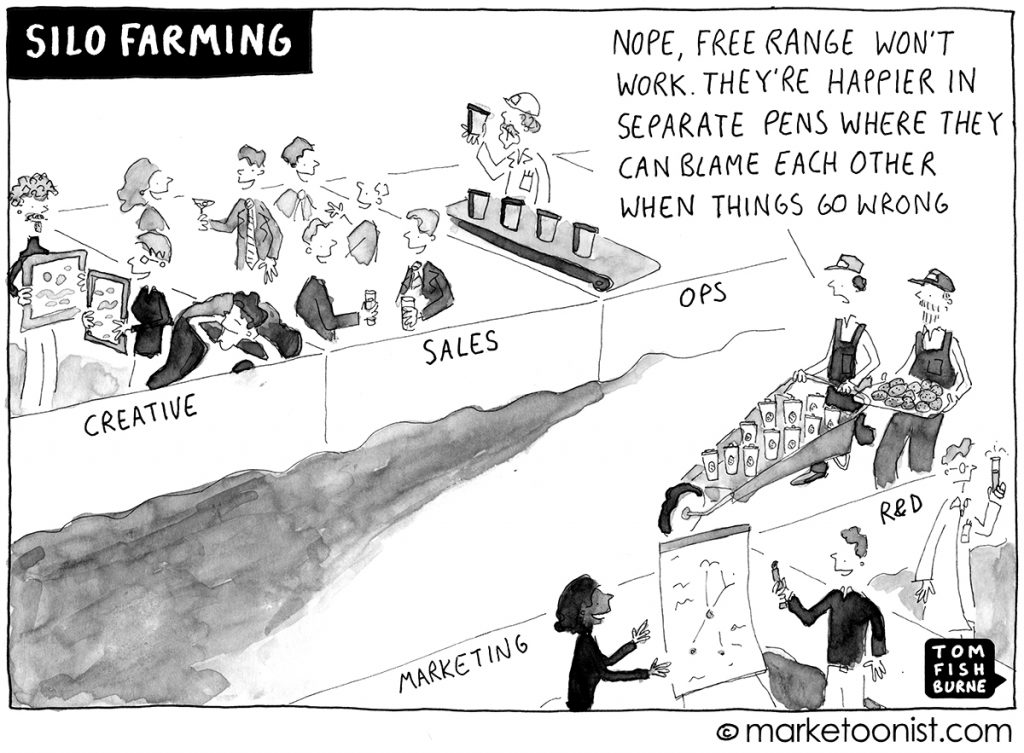

It’s generally accepted that inflexible hierarchies and structures encourage silo mentality. Even though highly specialized silos (e.g. teams and departments) are easy to manage and are great for team work, silo mentality also includes many unwanted behaviors. behaviors such as the desire to withhold information from other departments, the hoarding of resources or the lack of cross-departmental communication, that are very damaging to the learning ability of an organization and are huge barriers to external collaboration. What makes matters even worse, are incentivized compensation models based on functional silos.

"Compensation drives behavior!" This basic understanding can be found in almost every company. Salaries are coupled to specific annual objectives and KPIs, which in turn are regularly reviewed by managers. And these objectives are not only broken down for each individual employee, but also for each department. Incentives promote goal achievement of employees within their own sphere of influence - at least in theory. In reality this leads to “Functional Silo Syndrome”, a term coined by Phil S. Ensor in 198830. It basically states:

“Suboptimization of an organization's goals due to members of specific functions developing more loyalty to the function's group goals than to the organization's goals.”

In plain English: Your employees will naturally have more loyalty to his or her silo (e.g. department, team members) than the overall company, especially if you compensate employees based on their silo. It’s human nature. Therefore, in order to promote cross-functional teamwork and to break up your silos, you have to get rid of separate P&Ls (Profit & Loss) per silo (often done by division or department). You can’t demand cross-functional teamwork if, at the same time, you’re compensating your employees based on their functional silos. It’s highly contradictory from the perspective of the employee. It’s also foolish to give salespeople incentives to push disruptive products. Disruptive products require disruptive channels!

So how would an organization look like that encourages cross-functional teamwork, mitigates the innovator’s dilemma (at least to a certain extent) and is able to jump onto successive S-Curves over and over again?

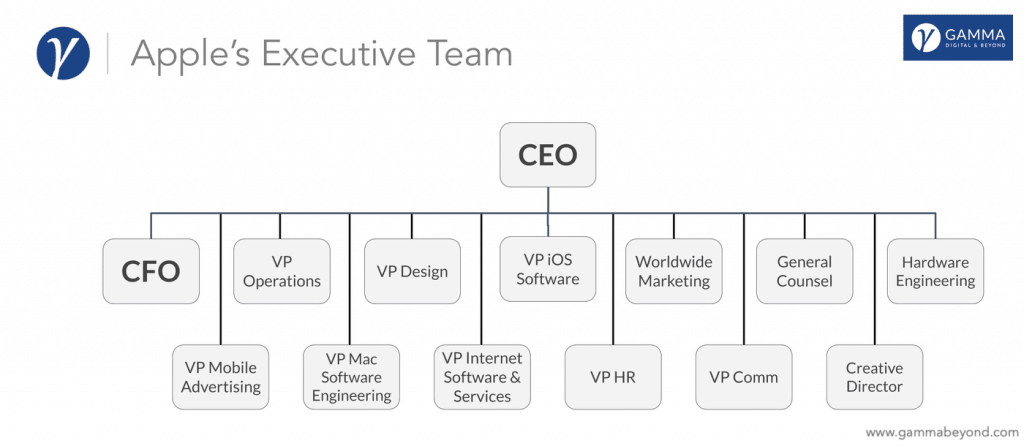

We don’t have to look far to see how Apple is structured (see Apple’s org chart below). While Apple undoubtedly still maintains a traditional hierarchy, it does boast a few elements from other organizational structures, that are interesting to note.31

Notice how Apple doesn’t have business heads like a “Head of MacBook”, iMac, iPad, iPhone, Apple TV etc.? You won’t find these product names in their org chart.

Expertise-based organization is another important feature of Apple’s organization. Each product within Apple’s portfolio such as MacBook, iPad, iPhone, Apple TV etc. is a direct result of collaboration of expertise-based groups (e.g. hardware engineering).

But the key thing to note here is that Apple has a single, unitary organizational structure32 with just one P&L. This has been arguably foundational to Apple’s success, which allows them to focus on the end-consumer instead of individual products. Many companies like to pretend they put the customer first, but very few truly live by that mantra. Apple basically builds it into their DNA. Or should I say P&L? So it shouldn’t come as a surprise that Steve Jobs re-organized Apple in this way on his return in 1997.

Of course, Apple’s organization has been subjected to various modifications since Tim Apple...I mean Tim Cook took over as CEO in 2011. Some of these changes included the decentralization of decision making to a certain extent in order to encourage innovation and creativity throughout the company. Nevertheless, the structure remains largely hierarchical.

Now, this isn’t to say that Apple doesn’t have its fair share of problems, but we can still learn a few things from one of the most innovative companies out there - one that has disrupted several industries over the last decade.

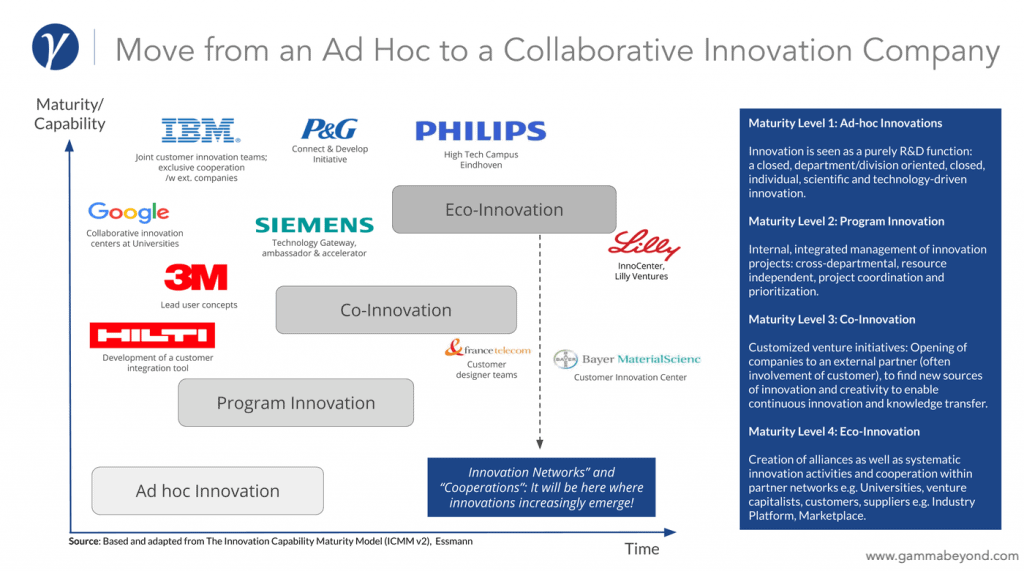

4. Move Towards a Collaborative Innovation Company

As the pace of product life cycles and the pressure to innovate increases, it’s harder than ever for companies to stay ahead of the competition. Businesses are struggling to manage complexity as a result of more and more technologies converging. It’s become virtually impossible for any company to compete by itself, requiring organizations to not only improve their innovation capability, but also their level of cross-organizational collaboration. It’s what Dr. Heinz Erich Essmann classifies as maturity level 4 or eco-innovation in his “Innovation Capability Maturity Model”.

Eco-Innovation is the forging of alliances and the pursuit of systematic innovation activities and cooperation within partner networks such as universities, venture capitalists, customers, suppliers etc.

Philips has recognized the need for such a model early on. In 1998, Philips established the Philips High Tech Campus Eindhoven in order to combine all its international R&D activities into single location. And in 2003 they even went a step further, opening up the campus to other companies to boost the interaction between people with different technical backgrounds.

The High Tech Campus Eindhoven is a high tech center and R&D ecosystem, home to more than 140 companies and institutions, comprising over 10,000 product developers, researchers and entrepreneurs with over 85 nationalities. The campus attracts companies and research institutes from various industries including nanotechnology, embedded systems, pharma, life sciences, as well as security and encryption.

The Financial Times, Fortune, Forbes and others have praised the Campus Eindhoven as one of the best locations in the world for high tech venture development and startup activity. And as such, it’s not hard to predict that it will be such models where innovations increasingly emerge in the future.

5.3 Practical Tips for (Senior) Executives

Before we wrap up this chapter, I will provide some additional tips that will help you when working with disruptive technologies.

1. Determine If Your Idea Has Disruptive Potential

Ask yourself these three questions, to determine whether your idea has any disruptive potential or when trying to change a sustaining innovation into a disruptive idea for greater growth potential.

A. Does it have low-end disruption potential?

- Can you identify customers at the low-end of the market, who would be willing to purchase a product33 with less (but good enough) performance or features if they could buy it for a cheaper price?

- Is there a business model where you can earn sufficient profits at lower prices in order to acquire business of over-served customers at the low-end?

B. Does it have new-market disruption potential?

- Are there potential customers (non-consumers) who have not had the money, equipment or skill to do a certain task themselves and have therefore gone without it altogether or have needed to hire someone with expertise to do it for them?

- Do customers need to visit a centralized location (physically or virtually) in order to use a product or service?

C. Does it disrupt at all?

- Is your idea disruptive to all relevant incumbents?

If your idea appears to be a sustaining innovation to one or more players, the chances will be stacked against you, and you then entrant, will be unlikely to win this battle.

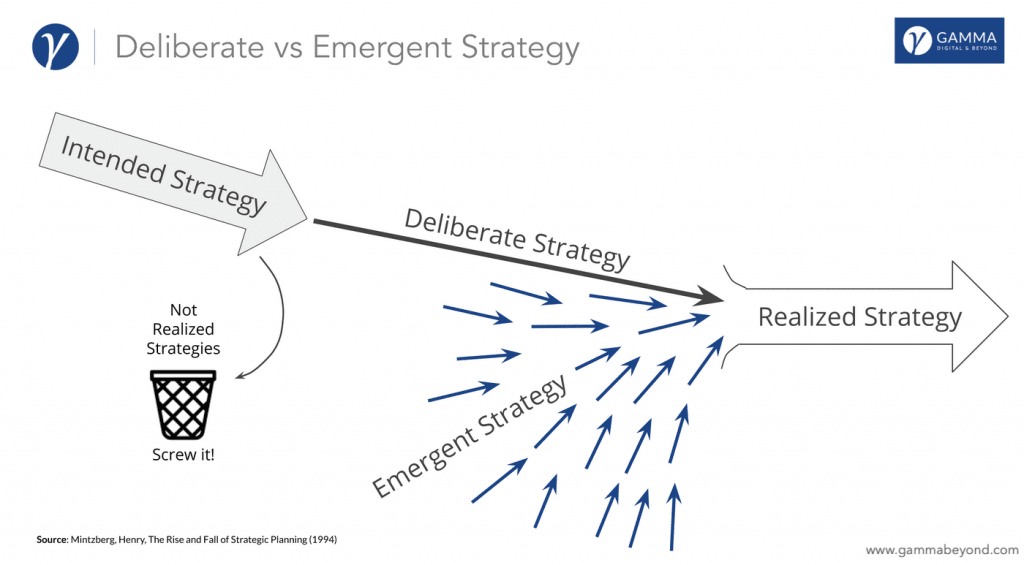

2. Apply Emergent Strategies for Disruptive Innovations

When executives decide on what strategy to apply for a new venture, they often miss the more important question:

What process will be used to define the appropriate strategy?

Because innovative ideas are inherently ambiguous, the question of how to formulate the strategy becomes more important. There are two different processes for strategy formulation: deliberate and emergent.

Deliberate strategy is the most commonly used and takes a “top-down” approach. It also tends to be very analytical, meticulous and derived after analyzing factors such as market segment and size, customers, competition, projected financials etc., after which the strategy is then (in the best case) realized (realized strategy). This approach works in environments where three conditions are met:

- All the important details required for success are included and are fully understood by those who implement the strategy.

- If collective action is necessary, then it must also make sense to every employee within their context.

- Expected outcomes should be influenced by external factors (e.g. political, technological or market) as little as possible.

It’s obvious that meeting all three conditions in reality is difficult. The environment and markets that companies operate are constantly evolving.

That’s why emergent strategy assumes that you cannot meet all of these conditions and must adapt from the original plan, which was not expressly intended from the start. Essentially, it’s the cumulative effect of all the day-to-day prioritization and investment decisions made by middle management and employees, also known as a bottom-up approach.34 And because of this, you can’t deduce a company’s strategy by simply looking at what goes into it, but by what comes out of the resource allocation process.

Emergent strategy should be used when the future is hard to predict and it’s still unclear what direction the company should take. This generally tends to be the case during the early phases of a company. Startups and entrepreneurs rarely get their strategies right the first time - something we’ve seen from our previous Thermondo example. They had to pivot multiple times to “get it right”.

Therefore, it’s essential to learn from emergent sources what is working and what is not, feeding the learnings back into the process and responding to an evolving reality rather than focusing on a stable fantasy. This is done by testing the validity of the most critical assumptions (also called “validated learning”). The key is to generate learnings quickly, with as little expense as possible, by validating or invalidating the most important assumptions.